Elizabeth Rosenberg, Assistant Secretary for Terrorist Financing & Financial Crimes

Eric Van Nostrand, Acting Assistant Secretary for Economic Policy

A year ago at the G7 Summit in Elmau, the leaders agreed to pursue a policy to cap the price of Russian oil to prevent Russia from continuing to earn a wartime premium. The price cap policy is a novel tool of economic statecraft designed to achieve two seemingly contradictory goals: restricting Russia’s oil revenues while maintaining the supply of Russian oil. Meeting these goals would make it harder for Russia to fund its brutal war in Ukraine while keeping energy costs down for consumers and businesses around the world. Nearly six months after implementation, the price cap is achieving both goals. We will continue to monitor dynamics in the global oil market going forward and adjust as necessary in support of these goals.

Russian exports have continued to flow, contributing to global oil market stability. Even as global oil prices have remained stable, the price of Russian oil has fallen significantly—driving down the Kremlin’s revenue. Immediately after the invasion, Russia received windfall profits on an oil price spike created by its war in Ukraine. But today, the price cap policy is taking that windfall off the table, which allows for low- and middle- income countries to purchase oil while at the same time making it increasingly challenging for Russia to finance its aggression.

In this post, we review how the price cap policy works and how it is accomplishing these twin goals.

How the Price Cap Works

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last February, the G7 committed to phasing out its reliance on Russian energy. We each took steps over time to ban the import of Russian products, notably oil. When the EU joined the US, UK, Canada, and others in banning imports of oil and petroleum products from Russia, they took steps to also prohibit services in support of the shipment of such fuel. Many analysts predicted that this total maritime services ban could have led to skyrocketing global oil prices. Investors widely recognized that oil prices could have surged to upwards of $150 per barrel, exacerbating global inflationary pressures. To mitigate these consequences, the G7 and Australia aligned with the EU to ban services related to the movement of Russian oil and petroleum products unless they were purchased below a price cap. Given the leading role the G7 plays in such services – from insurance to shipping to finance – this restriction has worked to limit Russia’s ability to profit from its war while promoting stability in global energy markets.

The price cap policy works by allowing companies based in Coalition countries to continue providing maritime services for the transport of Russian oil only if that oil is sold at or below the price cap level. Companies based in Coalition countries have historically accounted for around 90 percent of the market for relevant maritime insurance products and reinsurance. Traders, brokers, and importers depend on these services to trade, and vessel owners rely on insurance to protect their ships. Moreover, almost all ports and major canals require ships to carry protection and indemnity (P&I) insurance. If Russian exporters or importers of Russian oil want access to the Coalition-countries’ service providers, Russia must sell the oil at or below the price cap level. At the same time, the price cap affords greater leverage to purchasers operating without these services. These purchasers can use the price cap to negotiate better prices and pay less for Russian oil.

The price cap policy incentivizes the continued sale of oil and petroleum products on to the market at a steep discount from Russia’s wartime premium. In December 2022, the Coalition set the price cap on Russian crude oil at $60 per barrel. Immediately following its illegal invasion, Russia was earning over $100 per barrel on its oil sales, with world spot prices rising higher than $140 per barrel in the spring of 2022.According to data from the International Energy Agency (IEA), since the Russian oil price cap has been put in place, the average price of Russian Urals crude oil has been below $60 per barrel on a monthly basis.

Despite the complexity of the issue and the speed at which the Coalition needed to work, every Coalition country successfully implemented new coordinated laws and regulations. In addition, in February, the Coalition built on its success with the Russian crude oil cap by imposing a $100 per barrel price cap on Russian petroleum products, such as diesel, that trade at a premium to crude and a $45 per barrel price cap on Russian petroleum products, such as fuel oils, that trade at a discount to crude. Extensive consultations with shippers, traders, insurers, financers, and other market participants ensured that the price cap policy works within the contours of the global oil trade and that industry was able to implement smoothly at the outset, avoiding disruption to global energy markets.

The price cap policy benefits low- and middle- income countries. To be clear, Coalition members have prohibited almost all seaborne oil imports from Russia and are not themselves benefiting directly from Russian sales at the capped prices. Instead, the direct beneficiaries are mostly emerging market and lower income countries that import oil from Russia. Even for countries who are not using Coalition services, the price cap creates leverage to demand lower prices from Russia. These nations receive drastically lower prices than they did in the first few months after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The policy has thus lessened the negative global spillovers from Russia’s war and has been financially helpful for a number of vulnerable countries.

Economic Impact

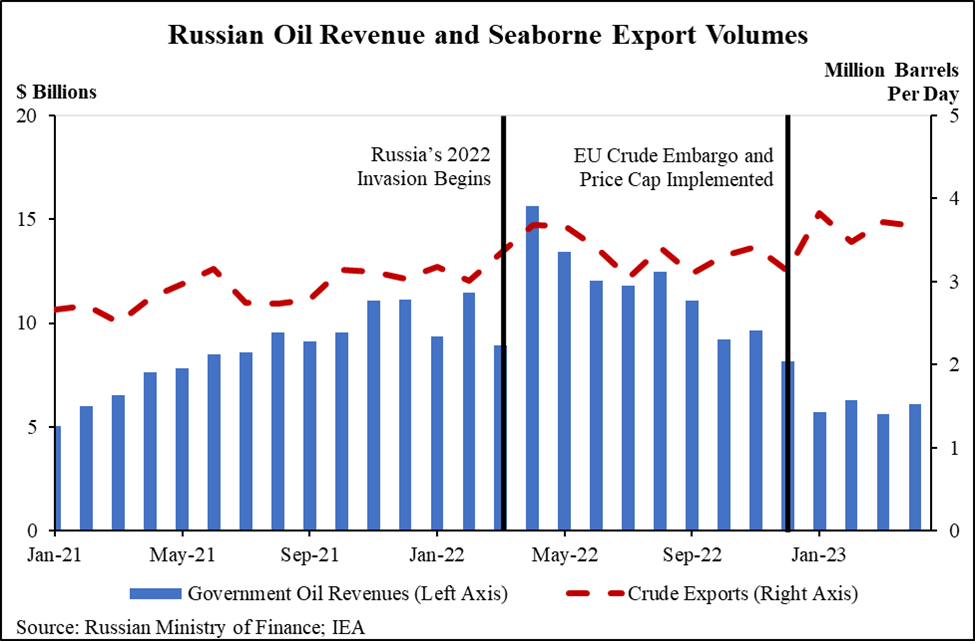

Following the implementation of the price cap policy, Russia’s oil revenues have fallen substantially compared to both pre-war levels and the elevated level at the onset of the war. According to the Russian Ministry of Finance, federal government oil revenues from January–March of 2023 were over 40 percent lower than a year prior. Before the war, oil revenues constituted 30–35 percent of the total Russian budget. In 2023, oil revenues have fallen to just 23 percent of the Russian budget. This decline in revenue has occurred despite Russia’s exporting roughly 5 to 10 percent more crude oil in April 2023 compared to March 2022.

Despite selling a consistent volume of oil, Russia makes far less revenue on each barrel because its oil now trades at a significant discount relative to Brent crude, the global benchmark oil price. Before the war, Russian crude oil traded at a discount of just a few dollars per barrel relative to Brent. In recent months, official price reporting agency data has shown that Russian Urals crude oil has traded at a discount of as much as $25-$35 per barrel less than Brent. The price cap mechanism gives importers leverage to negotiate steep discounts on their trades with Russia, evidenced in public reporting.

In response to the price cap, Russia has been forced to alter the way it taxes oil such that it institutionalizes the discounted value of Russian crude—essentially writing into law the steep discount the price cap has helped cement. This new taxation has the potential to threaten Russia’s future oil production capacity by reducing the incentive for companies to invest in equipment, exploration, and existing fields. This change comes on top of the impacts already being felt by U.S. sanctions and export controls against Russian energy firms.

Lastly, senior Russian economic officials have openly acknowledged that the price cap is hurting their ability to fund their war and prop up the Russian economy. Finance Minister Siluanov cited the price cap as a driver of reduced tax revenues and the expanded 2023 budget deficit. Analysts at Russia’s central bank have admitted that the price cap and EU sanctions present “new economic shocks” that could “significantly reduce” Russia’s economic activity. Meanwhile, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak said that “difficulties” from the EU embargo and price cap had not impeded overall volumes for crude oil exports and shipments, signaling that the lower price Russia is receiving is reducing revenues.

At the same time, roughly constant quantities of Russian oil have remained on the global market. Since the Coalition implemented the price cap policy, Russia has exported crude and refined products at pre-war volumes. Accordingly, global energy supplies have remained stable, contrary to widespread market expectations. In early February, Russia threatened a modest production cut, but seaborne export volumes have remained consistent. Markets also reacted tepidly to Russia’s threat, recognizing Russia’s incentive under the price cap to continue exporting at current volumes. Recently, Russia backtracked on a December decree banning price cap compliant trades. We will continue to closely monitor the market to ensure stability going forward.

Despite widespread initial market skepticism around the price cap, market participants and geopolitical analysts have now acknowledged that the price cap is accomplishing both of its goals.

- Fatih Birol, IEA Executive Director, said price caps on Russian oil have achieved the objectives of both stabilizing oil markets and reducing Moscow’s revenues from oil and gas exports. The IEA has also concluded that the EU’s import bans and price caps have caused Russia’s oil export revenues to fall sharply.

- According to S&P Global, “the US-led price cap policy has proven surprisingly effective at keeping oil on the market, despite EU import bans and G7 shipping sanctions.”

- Ben Cahill of the Center for Strategic and International Studies concluded, “[policymakers] are getting what they wanted: a well-supplied market with Russia getting less revenue.”

- Helima Croft of RBC Capital Markets stated, “… Russia seemingly was economically incentivized to keep selling their oil, and all indications are that refiners in India and China are abiding by the cap.… So right now, we’ve not seen yet a major Russian oil supply disruption.”

- Raad Alkadiri of Eurasia Group summarized that “[i]f the goal of Western powers was to have their cake and eat it too, then the cap is presently working as planned…Russian flows have been diverted but not disrupted for the most part, and prices have not risen.”

- Because of the plunge in its energy revenue, Russia, according to Bloomberg, has been forced to triple its foreign currency sales in recent months in order to finance its budget deficit. Russian energy revenues have declined to a one-year low after the imposition of the price cap. Bloomberg Economics estimates that by the end of the year, Russia will have to sell nearly a quarter of its sovereign wealth fund’s liquid assets.

The Coalition, including the G7, EU, and Australia, has been united throughout the process of imposing the price cap policy. The Coalition achieved a formidable task: within six months, the world’s economic powers rallied around a new tool of economic statecraft designed to apply economic pressure to an actor who has egregiously violated international law, all while preserving the effective functioning of worldwide energy markets and the global economy.

Going forward, we remain committed to upholding the price cap policy. The Coalition will continue to coordinate to ensure effective monitoring and enforcement of the policy, including countering evasion of these caps while avoiding spillover effects and maintaining global energy security. We are already taking steps to do this by providing additional guidance identifying red flags for possible price cap evasion and sharing best practices to assist good-faith actors.

The work is not over until Russia’s brutal invasion ends. The United States will continue to work with our Coalition partners to ensure the continued success of the price cap policy while further combatting Russian aggression.