The United States, along with an international coalition of over 30 allies and partners, has imposed sweeping sanctions, export controls, and other economic measures since the start of Russia’s unprovoked war against Ukraine. Since February 2022, these measures have made it harder and costlier for the Kremlin to obtain the capital, materials, technology, and support it needs to sustain its war of aggression.

Fast Stats

- Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has added over 2,500 Russia-related targets to the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN) List[1] since February 2022, including approximately 2400 individuals and entities, 115 vessels, and 19 aircraft.

- Those designated range from senior Russian government officials, including President Vladmir Putin, to high net-worth individuals whose wealth is tied to the Russian state, leaders in revenue-generating sectors, and supporters of the military-industrial complex.

- Over 80% of Russia’s banking sector by assets are under U.S. sanctions, including the top 10 Russian-owned banks.

- All members of the Russian State Duma (450) and the Federation Council (170) have been sanctioned, as well as 47 Russian governors.

- OFAC has added over 600 targets to the SDN List tied to Russia’s military-industrial complex, including major Russian military manufacturing firms such as State Corporation Rostec, Tactical Missiles Corporation JSC, and NPK Tekhmash OAO, as well as third-country providers of key inputs.

-

- OFAC has imposed five rounds of sanctions on Iranian producers of UAVs, targeting 28 individuals and entities.

- Since February 22, 2022, Treasury and State have designated over 200 targets associated with Russian sanctions evasion, spanning across Europe, Africa, and Asia, including key transshipment jurisdictions in the Middle East, the Eurasian Economic Union, and East Asia.

-

- In addition, over 60 family members of Russian elites have been designated. Moving or hiding money through family members is a known practice of those trying to evade sanctions.

- Treasury’s Russia-related actions had significant downstream effects in Belarus, which has supported and facilitated Russia’s invasion. The Belarusian economy is highly dependent on key Russian financial institutions and their subsidiaries; OFAC has sanctioned nearly one-fifth of Belarus’ financial sector.

- OFAC has targeted Russia’s malign activity globally, using a wide range of authorities to sanction entities and individuals in over 40 jurisdictions. This includes also leveraging sanctions authorities related to Belarus, Central African Republic, Iran, malicious cyber activities, and human rights abuse and corruption (Global Magnitsky).

- OFAC has identified nearly a dozen sectors of the Russian Federation economy, allowing sanctions to be imposed on any individual or entity determined to operate or have operated in those sectors and expanding the United States’ ability to swiftly impose additional economic costs on Russia for its war of choice in Ukraine. Sectors include metals and mining, quantum computing, accounting, trust and corporate formation, management consulting, aerospace, marine, electronics, financial services, technology, and defense and related materiel.

Private Sector

- More than 1,000 foreign companies reportedly have ceased or curtailed their operations in Russia since the start of the war, stifling investment and industrial activity.

- To help the compliance community effectively implement U.S. sanctions, OFAC has issued 134 new and 104 amended Frequently Asked Questions.

- To minimize the unintended negative consequences of U.S. sanctions on Russia while ensuring a high degree of impact on Russia, and particularly to protect and preserve agricultural, humanitarian, and energy transactions, OFAC has issued 68 new and 40 amended general licenses.

- Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) FinCEN issued four alerts, one advisory, and a trends analysis to U.S. financial institutions identifying trends and red flags associated with Russian illicit finance, including corruption and kleptocracy, financial activity of Russian oligarchs, sanctions and export controls evasion and the abuse of real estate, luxury goods, and other high-value assets.

Price Caps

- The G7+ price caps on Russian-origin oil and petroleum products are important tools to reduce the revenue Russia receives to fund its illegal war in Ukraine, while also supporting energy market stability, which is particularly important for low- and middle-income countries hit hardest by the effects of Russia’s war.

- In December 2022, the 27 Member States of the European Union (EU), the members of the G7 (the United States, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and United Kingdom) and Australia – collectively, the Price Cap Coalition – adopted a cap of $60/barrel for crude oil of Russian origin. In February 2023, the price cap coalition set caps on refined oil products. These price caps are subject to ongoing review.

- The price cap policy allows services providers in the Coalition to participate in trade of seaborne Russian-origin oil only if the oil is traded below the cap—and provides importers outside the Coalition with the leverage to negotiate heavy discounts on Russian oil.

Multilateral Efforts

- To continue close collaboration with partners and allies on sanctions, the price cap, and other economic measures, starting in November 2021, senior Treasury officials have taken over 80 trips to 31 countries to coordinate on international sanctions so far.

- The multilateral Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs (REPO) Task Force, consisting of Finance, Justice, Home Affairs, and Trade Ministers from Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Commission has immobilized about $300 billion worth of Russian Central Bank assets.

- Collectively, REPO members have blocked or frozen tens of billions of dollars worth of sanctioned Russians’ assets in financial accounts and economic resources.

- REPO members have seized, blocked, or frozen luxury real estate and other luxury assets owned, held, or controlled by sanctioned Russians, valued in the many billions of dollars.

Key Impacts

Sanctions and export controls have been a key driver of major output declines, most notably in sectors with military applications—including automotive, aerospace, and electronics. Imperfect attempts at parallel import mechanisms and substitution from Russian allies have not succeeded and may limit future growth.

Russia’s military-industrial complex and defense supply chains have been significantly degraded by sanctions and export controls.

Depletion of Military Supplies

- 9,000 pieces of military equipment have been lost and difficult to replace.

- Russia is facing shortages of essential components for tanks, aircraft, and submarines and is running out of serviceable munitions.

- Russia has probably lost as much has 50% of its supply of tanks and has been forced to reactivate outdated Soviet-era T-62 tanks.

- Officials have touted import substitution, but in the defense industry, dependency actually increased since 2014.

Defense Manufacturing Under Pressure

- Production shutdowns have occurred at key defense-industrial facilities, including for tanks and micro-electronics.

- The share of defective microchips shipped from China is up from 2% to 40%.

Declining Defense Exports

- Customers are canceling or rethinking deals worth hundreds of millions of dollars because of sanctions risk or poor weapons performance in Ukraine and Rosoboronexport, the sanctioned state-owned defense conglomerate, has faced supply chain challenges.

- Prior to the war, Russia was the second largest arms exporter in the world. Now, Moscow is expecting a 25% decrease, or more, in revenue for 2022.

- Plans to market a next-generation heavy fighter bomber to foreign buyers have collapsed.

Technology

- Before the war, Russia’s plan was to build a high-tech military for future conflicts, including a focus on AI technology.

- However, sanctions and export controls have cut off Russia from much of the world’s supply of microchips, including from TSMC, the Taiwanese company that manufactured chips developed needed for Russia’s high-tech industries and defense sector.

- The ability to manufacture locally is significantly constrained. For example, only 30% of machine tools are Russian-made and local industry doesn’t have the capacity to cover rising demand.

Reliance on Inferior Suppliers

- Chip restrictions may cause Russian weapons to fall a generation behind or more due to forced reliance on less sophisticated Chinese or Southeast Asian alternatives.

- Russia has had to buy inferior weapons from places like Iran, North Korea, and Belarus.

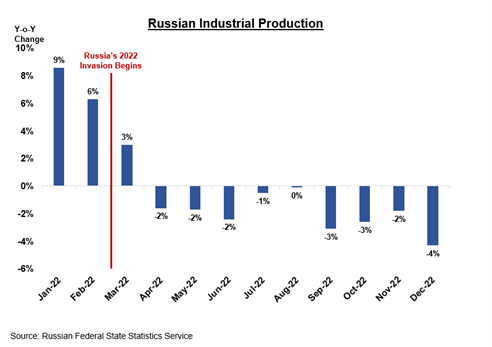

Russian industrial output has contracted for nine consecutive months, underscoring the effects of Western sanctions and labor shortages. Russia’s advanced manufacturing industries are falling behind due to sanctions and export controls and may not recover for years or decades.

Airline Industry Under Pressure

- Russian airlines, including state-run Aeroflot, were forced to strip aircraft for spare parts.

- Half of the components and technologies used in the Russian aircraft industry in 2021 originated from foreign countries. 95% of Russia’s passengers were previously carried on foreign-made planes; the lack of access to imported parts will lead the fleet to shrink as planes go out of service.

- Russia has been forced to turn inferior suppliers like Iran for critical parts, undermining the long-term viability of its aircraft fleet.

Automotive Manufacturing in Decline

- Car production was down 67% in 2022, the lowest level since collapse of the Soviet Union, driven in part by exodus of global carmakers.

- Car sales were down 59% in 2022.

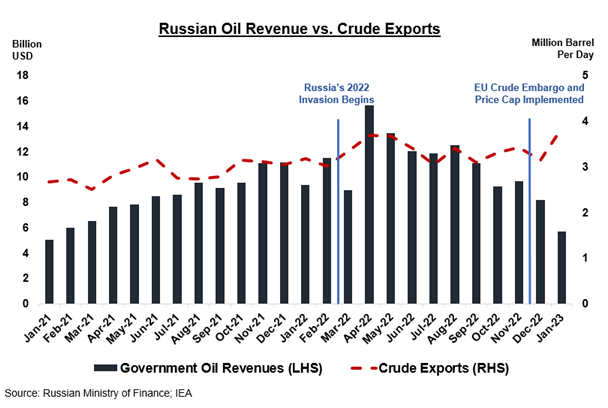

In the early wake of the price cap, Russian oil revenues have fallen to their lowest level in two years, while oil export volumes are at new highs.

- Just over two months after implementation, the price cap on Russian crude oil is already achieving its twin goals: limiting Russian revenue while avoiding a supply disruption in global markets.

- According to data from the Russian Ministry of Finance, in January 2023 government oil revenues were nearly 60% lower than March 2022—just after the invasion—despite oil Russian exports rising over 15%.

The value of Russian crude has eroded as the price cap gives importers in emerging markets leverage to negotiate discounts.

- Russia is being forced to sell its flagship crude, Urals, at larger and larger discounts as buyers worldwide use their increased bargaining power against Russian exporters.

- Since the December 5 price cap implementation, Urals discount to global benchmarks has expanded to more than 30%.

Russia’s Fiscal Position Continues to Deteriorate.

- The Kremlin sought to mitigate economic pressure in 2022 through increased government spending, high energy export revenues, and aggressive capital controls.

- However, vulnerabilities in the economy could intensify in 2023 as energy revenues come under pressure from Western restrictions, while increased security expenditures and weaknesses in the real economy continue to compound.

- Russia’s budget deficit in 2022 (2% GDP) was almost 3x pre-war expectations.

- G7 actions have limited Russia’s access to excess energy profits as the price cap cuts into oil export revenues and Gazprom’s gas exports sit at their lowest level of the post-Soviet era.

- In December and January, Russia relied on foreign reserve sales from the National Wealth Fund to cover these record deficits.

- However, around half of Russia’s foreign reserves have been immobilized by G7 jurisdictions, constraining Moscow’s ability to support their economy and finance deficits in this manner.

- Some analysts have speculated that if the NWF continues to be used in this way Russia could deplete its liquid assets in the next 2-3 years.

- The Russian financial sector, which was targeted directly by international sanctions following the invasion of Ukraine, reported a 90% decline in net profit year-on-year in 2022.

[1] For purposes of this fact sheet, totals include any sanctions designations by the U.S. Department of State that are implemented by OFAC and added to the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN) List. This does not include, for example, State Department visa restrictions, or Commerce Department additions to their Entity List.