The two monumental Columbian display frames that hang in Treasury’s North Lobby appear as if they were created specifically for this space. However, this is not the case. Rather, the frames have a rich history from their creation for the 1893 World’s Fair, the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, to their restoration and placement in the Treasury building (Figure One: Restored World Fair frame in the North Lobby, 2013).

Missing their interior displays, the two frames were discovered in a government warehouse in 1985. Initially, the frames' origin and purpose were a mystery. Upon closer investigation, the frames’ central shield was identified as the coat of arms given to Christopher Columbus by Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain. This clue helped determine that the frames were part of the Treasury Department's Bureau of Internal Revenue exhibit at the World's Columbian Exposition, an international fair celebrating the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus' discovery of America (Figure Two: Restoration of Coat of Arms on Columbian Frame, 1989).

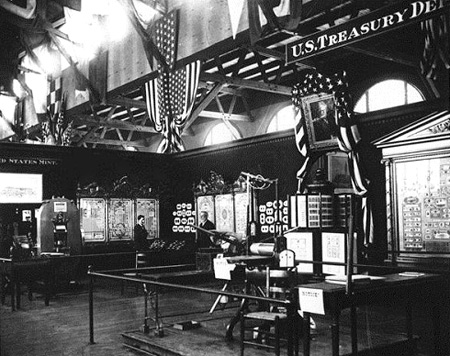

Congress required that the seven government departments submit exhibits to the Columbian Exposition which would be housed in the “Government Building,” one of twelve major exhibit halls at the fair. The buildings for the fair were all painted white, hence the fair’s nickname, “The White City.” The Treasury bureau displays included exhibits from the Life-Saving Service, the Marine Hospital Service, the Office of Weights and Measures, the Bureau of Internal Revenue, the U.S. Mint, the U.S. Lighthouse Establishment and the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (Figure Three: The Court of Honor, 1893).

A committee was appointed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing who decided to exhibit specimen frames, similar in composition to previous displays for world’s fairs. Initially, one thousand dollars was appropriated for the exhibit but that sum was ultimately deemed insufficient and additional funding was obtained.

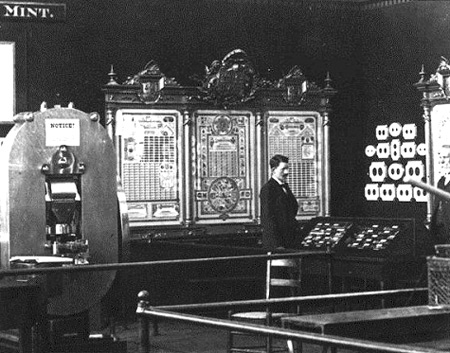

The bureau displayed currency in its frames to demonstrate the extraordinary skill of its engravers and the advanced technology of its printing process. The committee was very careful in its selection of notes for the interiors to avoid duplication with the Treasury Register’s office who was also exhibiting display frames at the World’s Fair. In addition to specimen displays by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the Mint produced a scale model of the Treasury building made of newly minted souvenir coins.

The currency display frames that were created for the 1893 Columbian Exposition have their origin in “fractional currency shields,” display cases housed in banks and post offices beginning when currency was first printed by Treasury in the 1860s. The displays became necessary when a unified national currency was created and counterfeiting became problematic.

This type of display frame was further developed and popularized with the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia held in 1876. At this fair, the display frame became extremely decorative, intended for aesthetic appreciation as well as for educational purposes. One surviving example, in the Treasury collection, clearly shows how the Columbian frames evolved from the 1876 Centennial Exposition prototype, both in the style and monumentality of the frame and the artistic presentation of its contents.

Historic photographs document the currency display frames as they were exhibited at the Columbian Exhibition. The fair photos show that three frames were manufactured for the exposition, with only two frames surviving today. The photos reveal that the original ornament on the frame was much more elaborate than that seen today. The Columbian Arms included a globe and cross over the knight’s visor representing the extension of Christianity to the New World through Columbus’ voyage. This was originally surmounted by the classic American crest of an eagle and shield with stars and stripes with the emblems of war and peace, arrows and an olive branch. Two ribbons bearing the motto of Columbus and national motto were entwined across the top of the frame. The additional crest added nearly a foot to the height of the frame.

After their debut at the Columbian Fair, the frames were exhibited at the Tennessee Centennial Exposition (1897), the Buffalo Pan-American Exposition (1901), the St. Louis Exposition (1903), and the Alaska-Yukon Pacific Exposition (1909). The bureau did not retain the Columbian fair interior displays but had them for the subsequent fairs and exhibitions (Figure Four: Treasury Department Exhibit at the Tennessee Centennial Exposition. 1897).

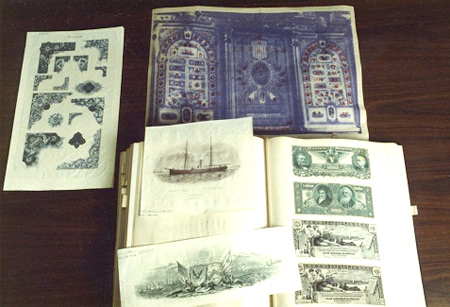

Historic photographs were found showing the frames as they were exhibited at the Columbian Exposition and subsequent exhibitions. By greatly enlarging the photographs, a numismatic expert was able to identify much of the currency, bonds, and stamps in the interiors of the original frames from the photos (Figure Five: Restoration and Conservation of Columbian displays, 1989).

Originally, the frames housed displays of stamps for tax on alcohol, tobacco, snuff, imported spirits, cigars, cigarettes and smoking opium. Following the 1901 Pan American Exposition, the displays were dismantled and rearranged with more current stamps, bonds and currency for the future expositions. For purposes of the restoration, researchers at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing used photographic evidence of the Treasury’s exhibit at the Tennessee Exposition to identify the frames’ contents and reproduce them (Figure Six: Treasury Department Exhibit at the Tennessee Centennial Exposition. 1897).

Ultimately, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing could now produce reproductions that would completely restore the frames accurately to any single exposition. One frame now highlights objects from the 1897 Tennessee Centennial Exposition while the second frame is a mixture of historical items available from BEP plates from the various expositions.

The Office of the Curator restored the historic frames and reproduced the interior currency displays. The frames were restored by removing several layers of over paint to reveal the original finish. Perhaps because they may have sustained damage traveling from fair to fair, at some point the frames were coated with bronze radiator paint. In 1989, this bronze paint was carefully removed revealing the original gold leaf finish (Figure Seven: Columbian Frame Restoration, 1985).

The historic dies and plates for all the currency, bonds, and stamps originally displayed in the currency frame were retained in the vault at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, and were used to replicate each of the originals by printing them on a 19th century hand-press. Because the plates and dies no longer existed or could not be found for the other frame, that display could not be replicated exactly. It is, therefore, composed of original bonds and reprinted currency produced after 1893. A graphic artist designed and assembled the currency displays using the historic photographs and models of other existing currency displays in the Treasury collection (Figure Eight: Printer at the BEP replicates display on 19th century hand-press, 1989).

The restored frames now hang in Treasury’s North Lobby, immediately adjacent to the Cash Room. Like the 1869 Cash Room, the frames symbolizing America’s financial exuberance during the gilded age. The reprinted notes represent the artistic achievements of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing while the frames themselves are magnificent examples of the framers’ and gilders art during the late 19th-century. Treasury is fortunate in being able to once again display the restored frames and share them again with the public, just as it did at the 1893 Columbian Exposition.