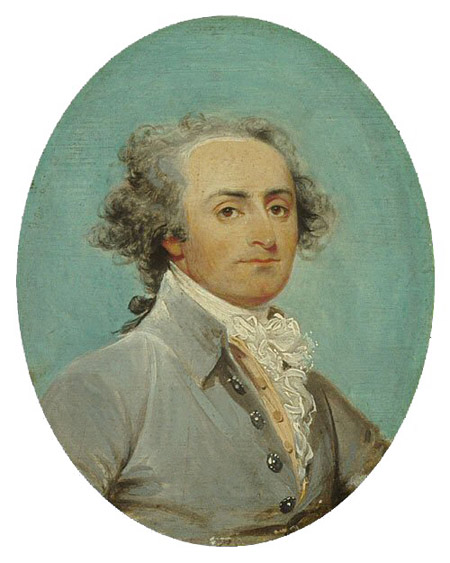

In the front parlor of the house she shared with her daughter, on H Street in Washington, Eliza Hamilton (Figure One: Mrs. Hamilton Portrait), the widow of Treasury Secretary Hamilton, displayed the most prized relics of her late husband.

According to Hamilton’s biographer, Ron Chernow:

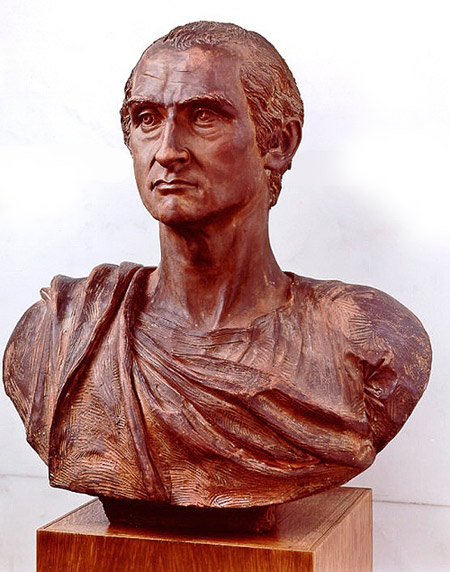

When visitors called in the 1850s, the tiny, erect, white-haired lady would grab her cane, rise gamely from a black sofa embroidered with a floral pattern of her own design, and escort them to a Gilbert Stuart painting of George Washington. But, the tour’s highlight stood enshrined in the corner: a marble bust of her dead hero, carved by an Italian sculptor, Giuseppe Ceracchi, during Hamilton’s heyday as the first Treasury secretary (Figure Two: Hamilton Bust). Portrayed in the classical style of a noble Roman senator, a toga draped across one shoulder, Hamilton exuded a brisk energy and a massive intelligence in his wide brow, his face illuminated by the half smile that often played about his features. This was how Eliza wished to recall him, ardent, hopeful, and eternally young. ‘That bust I can never forget,’ one young visitor remembered, ‘for the old lady always paused before it in her tour of the rooms and, leaning on her cane, gazed and gazed, as if she could never be satisfied.

The story of Treasury's Hamilton bust begins in Philadelphia where the capitol of the United States was temporarily located before its permanent move to Washington in 1800. It was here that President George Washington and the members of his cabinet resided and where a young Roman-trained sculptor, Giuseppe Ceracchi would find a fertile field of clients for his artistic endeavors. The fact that the young artist was particularly skilled in European Neo-classicalism was not lost on our founding fathers whose likenesses would be sculpted in the pose and style of the leaders of the ancient Roman Republic.

Born in Rome, the son of a goldsmith, Giuseppe Ceracchi distinguished himself at an early age at the Accadenia de San Luca (Figure Three: Giuseppe Ceracchi Portrait). With lofty career aspirations, he traveled to London in 1773 to work with an established Italian sculptor and soon was modeling architectural ornament and bas reliefs for the recognized Neo-classical architect, Robert Adams. During this period, Ceracchi executed allegorical figures and reliefs with historical and classical subject matter, as well as portrait statues and busts. His works were exhibited at the Royal Academy between 1776 – 1779 and his subsequent failure to be elected to the Academy prompted him to leave England for Vienna and later Amsterdam, cities in which he spent most of the 1780s.

Interest in revolutionary causes as well as hope for governmental commission brought him to America in 1791, the first of two visits, the second in 1794 -5. Although his objective of executing an equestrian statue of George Washington as mandated by Congress in 1781 never materialized, he did solicit and win commissions from the most prominent Americans of the day. One of his clients, James Madison, described Ceracchi as “an artist celebrated by his genius.” Writing to Thomas Jefferson, the sculptor noted of James Madison that he would, “honor my chisel with cutting his bust.” Obviously, both artistic and verbal flattery worked to the artist’s advantage.

During his two American visits, Ceracchi executed twenty-seven heroic portrait busts of America’s most prominent leaders including George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, George Clinton and Treasury’s own Alexander Hamilton (Figure Four: Ceracchi Bust of John Jay). Despite his aspirations for a fully developed artistic career in America, Ceracchi’s artistic production remained in Europe. The artist modeled his patron’s likeness in clay, sending the terra cotta casts to Florence, Italy, where they would be rendered in white marble.

In this regard, Ceracchi’s original terra cotta model of Treasury Secretary Hamilton, now lost, was executed from life in 1791 or 1792. The artist’s iconic pose of Hamilton blended the neoclassical precepts in which he was trained, together with his personal revolutionary sentiments, depicting Hamilton proudly wearing the ribbon of the Order of the Cincinnati. In July 1792, Ceracchi wrote Hamilton that he was, “impatient to receive the clay that I had the satisfaction of forming from your witty and significant physiognomy.”

On returning to America in 1794, Ceracchi presented Hamilton with his marble likeness. It was not until March 3, 1796 that Hamilton paid the sculptor $620, in his expense book noting, “For this sum through delicacy paid upon Ceracchi’s draft for making my bust on his own opportunity, as a favor to me.” The sculptor recognized the importance of his artistic representation and signed the marble bust in Latin, “Executed in Philadelphia and copied in Florence, Executed by Joseph Ceracchi, 1794.” The sculptor also created additional marble copies from the plaster, including one acquired at the same time by Hamilton’s nemesis, Thomas Jefferson for the front hall of Monticello

The Ceracchi bust became the iconic likeness of Hamilton and was used extensively by artists for posthumous portraits. In 1805, John Trumbull, who had painted Hamilton from life, used Ceracchi’s bust as the source for his masterful, full-length portrait of the statesman that was commissioned by the City of New York and which the artist made copies (Figure Five: Portrait of Hamilton, John Trumbull, 1972).

rvsd.jpg)

Daniel Huntington, the acclaimed American artist and history painter, suggested the importance of Ceracchi’s Hamilton bust by including it in the background of his portrait of Hamilton’s grandson, Alexander Hamilton II painted in 1864. Daniel Huntington’s own portrait of Alexander Hamilton that hangs immediately outside the Treasury Secretary’s office is a copy after the John Trumbull portrait which is also derived from Ceracchi’s bust (Figure Six: Hamilton Portrait, Huntington, 1865).

The Treasury Department has played a leading role in perpetuating Ceracchi’s Hamilton bust as an American icon. In 1870, the bust appeared on the thirty-cent U.S. postage stamp (Figure Seven: Cent Stamp of Hamilton). Hamilton’s image, engraved by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing for the ten dollar bill, was taken directly from the Trumbull portrait and one scholar has noted that it, “represents the art of Ceracchi more than that of Trumbull.”

The Ceracchi bust, so prized by Eliza Hamilton, remained in the possession of Alexander Hamilton’s descendants until 1896 when it was bequeathed to the New York Public Library. The story of the Hamilton bust does not end with its acquisition by the New York Public Library. The original Ceracchi bust was both de-accessioned by the library and sold at Sotheby’s on November 30, 2005.

On May 10, 2009, another Hamilton bust came up for auction at Brunk Auctions in Asheville, N.C. It was described in the catalogue as “rendered, after Giuseppe Ceracchi, Italian, 1751 – 1801, unsigned, painted plaster, 24 inches, abrasions, sooty grime” and with a provenance, “Former Collection of a Mid-Atlantic Museum.” Several images of the Hamilton bust were posted on-line along with the brief condition report.

In reviewing the catalogue material, it became apparent that the same Mid-Atlantic Museum was de- accessioning a varied assortment of objects including a portrait bust of Don Camillio Borghese whose wife Pauline, the sister of Napoleon Bonaparte, was sculpted by the famous Italian sculptor Canova. A Hamilton bust after Guiseppe Ceracchi and the bust of an Italian nobleman provided tantalizing leads in determining the identity of the unnamed institution.

Following standard auction protocol, the Curator’s office contacted Brunk Auctions and requested more detailed photographs as well as additional information on its condition. Brunk provided the requested photographic documentation, including detailed shots of the back of the bust which showed the number, “1869.1.” (Figure Eight: Bust accession number, “1869.1”). The condition report confirmed that the bust was in excellent physical condition, the features of Secretary Hamilton somewhat obscured by a later paint. There were no major cracks or repairs only dirt and grime.

With the assistance of the Treasury Historical Association the Hamilton bust was acquired through Brunk Auctions for the Treasury sculpture collection. Now that the bust was Treasury’s, research into the object’s history could begin in earnest.

The investigation would start with the object’s provenance. In this case, the red number on the back of the bust offered a clue that would immediately link it to an institution. The red painted number, “1869.1” is what the museum world recognizes as an accession number. Typically, this number contains the year that the object was first recorded in the collection and here the date is 1869. The number “1” after the date signifies that it was the first accession in 1869.

Merrill Lavine, Treasury’s registrar, recognized the red painted accession number, “1869.1” has the script of a former Maryland Historical Society registrar. In an e-mail of May 11, 2009, Merrill wrote: “Not only is it MHS, Maryland Historical Society, but it jolted me back into remembering the exact day I cleaned the attic sculpture room, the second year I was there, in choking August heat.” Contacting the historical society’s registrar, Merrill was able to obtain additional information on the bust’s history.

According to the Maryland Historical Society’s records, the Hamilton bust entered the collection in 1868 and was formally accessioned in 1869. The records of the Maryland Historical Society document the donor. It was given by John H. Naff, a Baltimore auctioneer, who wrote “Recollections of Baltimore in 1851.” Where Naff acquired it is open to speculation. John Edgar Howard, a figure prominent in Maryland history, was a Colonel in the Continental Army and served as an aide-de-camp to Hamilton. Howard may have acquired the bust as a memento of his former commander. Howard’s estate was sold at auction three weeks after his death in 1827 and would have afforded Naff an opportunity to acquire the Hamilton bust if indeed Howard owned it. The subject headings of the sale note both “Interior Decoration” as well as “Portraits,” both categories that the bust could encompass (Figure Nine: Hamilton Bust, pre-conservation).

When the bust arrived at Treasury, it confirmed the condition stated in the Auction report, ”Flaking, abrasions, sooty grime, and chips to base.” What also became apparent was the fact that the bust had been repainted and the paint served to protect the original surface. The fact that the bust is made out of plaster was also a plus since, unlike busts made out of marble or bronze, abrasions and chips on plaster busts are much more forgiving (Figure Ten: Hamilton Bust, pre-conservation, profile view).

At this point the next step in the bust’s history is a formal condition’s assessment by a professional conservator. After a thorough assessment by a professional conservator it was determined that the condition of the plaster sculpture was structurally sound and flat on its base. That determination made, the outer paint layer was then removed. Fortuitously this layer was a white wash and could be removed with water using cotton swabs and pads, the standard tool of the conservator (Figure Eleven: Bust during conservation).

In the removal of the white wash, original inscriptions were discovered on the back of the bust which came to be read as the signature of the maker, “J. Lanelli, #234.” This inscription would prove significant in dating the bust and identifying other contemporary examples by the same maker. Another discovery made during the conservation was a break along the neck and shoulders which had been repaired. This break was made when the bust was originally fired since the interior hollow of the bust was filled with large masses of the original plaster that were used to reinforce the crack. That the firing crack was not a deterrent in marketing bust #234 suggests that the maker was anxious to get his product to market.(Figure Twelve: Hamilton Bust, progress during conservation).

Through the conservation process, the majority of the original finish was salvaged and paint losses and chips were filled with a synthetic plaster putty and sanded flush to the sculpture. In consultation with the conservator, it was decided to saturate the original paint layer with a protective coating to protect the newly exposed finish from dust and debris. With its original finish and inscription now restored, what do we know about Joseph Lanelli, the maker and his production of the Hamilton busts? (Figure Thirteen: Conserved bust).

In addition to the bust at Treasury, there are three other Alexander Hamilton busts attributed to Lanelli in public collections. The Henry Francis DuPont Winterthur Museum acquired a Hamilton bust that offers insight into the busts and its maker. Winterthur's Hamilton bust entered the collection in 1974 as a gift with an interesting provenance. The donor purchased it from a dealer in 1963 who acquired it from a private collector in 1941, who stated that they had purchased the bust in Florence, Italy

The Winterthur bust is not signed by “Lanelli” but does have the Latin inscription, “Made in Philadelphia and copied in Florence, Joseph Ceracchi, Maker, 1794.” It also has the stylized number, “No. 66.”. The inscription denoting the fabrication is the same as that found on the original Hamilton bust now in the Crystal Bridges Museum. The Winterthur Museum 1974 accession report also compared its bust with another example, “Despite the fact that one copy numbered “435” is extant, few of the Lanelli plasters have survived. Of those surviving examples, all are in institutional collections except two, of which this is one.”

The bust number “435” referred by the Winterthur report is one of two plaster Hamilton busts that are in the collection of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. The society was founded in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin and boosts a rich collection of artifacts. The dates that the busts entered their collection are in themselves significant: one bust was given in 1818 and the second bust, the one numbered “435” and signed by “J. Lanelli” in 1840. The bust, donated in 1818, has the identical Latin inscription as the one in the Winterthur Collection but is not signed or numbered by Lanelli (Figure Fourteen: Lanelli "435" bust of Hamilton).

Having identified this small grouping of three plaster busts with shared characteristics and numbers, what can we conclude about the bust’s origins? I would like to propose that Lanelli fabricated his plaster busts in Italy and then sold them in the United States through a now unknown retailer, probably in the Mid-Atlantic States.

There is one other source that sheds light into where the busts may have been fabricated and transported to the United States. That link is Thomas Appleton, who served as the United States Consul in Livorno, Italy, during the period that the Hamilton busts, in marble and plaster, made their way to American shores. Thomas Jefferson secured Thomas Appleton’s Consular position in 1797 and was one of a number of Americans who engaged Appleton to facilitate purchases of artwork from the Italian markets. It is from Jefferson’s correspondence that we learn that Giuseppe Ceracchi’s “bust of Genl Washington in plaster,” was in Appleton’s possession and “is the only original from which the statue can be formed.” Appleton had purchased the plaster from a fellow consul, William Lee, then at Bordeaux, who previously had engaged in the identical business of producing multiple from the model. Given Appleton’s proximity to Florence and the Ceracchi cast of Hamilton, his role in the production of the plaster busts with Lanelli is a distinct possibility.

With the bust now conserved to its original appearance, the question arises how to best exhibit it? As seen with Hamilton’s contemporaries, hung wall brackets and standing pedestals were the most conventional method of displaying busts in the 19th-century. Two examples of the use of hung wall bracket may be found in the old Supreme Court chamber of the United States Capitol and the dining room of Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. In each instance, the wall brackets are hung in bays, walls located between openings, either doors or windows. This is the method that was judged best for the Treasury bust in the Secretary’s Reception Room.

While there were no suitable brackets extant in the Treasury collection, late 19th-century archival photos document one very stylized bracket hanging in a workroom adjacent to a vault in the Treasury building. This particular bracket was used in ca. 1910 to display Treasury’s carved window eagle, one of the finest carved mid-19th century eagles in America and one that still graces the Treasury building (Figure Fifteen: Photograph of eagle bracket in Treasury). The bracket’s detailed photograph enabled the Curator’s office to reproduce a Treasury example that is stylistically appropriate for the classicalism of the Hamilton bust. The bracket serves as a platform for the Hamilton bust, exhibited in the Secretary’s Reception Room.

In conclusion, Treasury’s newly acquired Hamilton bust is a plaster copy made directly from the original terra cotta model taken from life by the Roman-trained sculptor Giuseppe Ceracchi. The bust was fabricated in Florence by Joseph Lanelli and shipped to the United States where it was marketed. It dates to the period, ca. 1805 -10, the number #234 suggesting that it was not made in the first group of busts that also bears the same inscription as that found on the original marble. The fact that the American Philosophical Society had acquired, through donation, a plaster copy in 1818 suggests an early date of manufacture. The conserved bust is now on display in the Secretary’s Reception Room, 3317, alongside other Treasury portraits and sculpture (Figure Sixteen: Hamilton bust in-situ today).