By: Deputy Secretary of the Treasury Wally Adeyemo

This week, the Treasury Department will host the third meeting of the Treasury Advisory Committee on Racial Equity (TACRE). TACRE is comprised of 25 experts drawn from academia, business, nonprofits, philanthropy, and other fields who help the Treasury Department ensure we are thinking about how our policies impact racial equity and hold us accountable for the commitments we’ve made. With Juneteenth approaching, this week’s TACRE meeting is an ideal time to take stock of our work to date.

As I look back at the last two-and-a-half years of the Biden-Harris Administration, I am proud of the way our actions have advanced racial and economic equity, from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARP) enacted in the early days of the Administration to the ways we have implemented the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) over the past few months. We have seen historic gains in employment and wages among Black and Hispanic workers, as well as on other key economic metrics.

To name just a few, both Black unemployment and the gap between Black and white unemployment recently reached their lowest levels on record. From 2019 to 2022, median weekly earnings increased 4 percent for Black workers and 2.4 percent for Hispanic workers after accounting for inflation.[1] And the Black and Hispanic supplemental child poverty rates—which account for government benefits—reached their lowest levels since 2009.[2]

But an underappreciated aspect of these policies designed to support those often left behind by economic policy is the impact they have on all working-class Americans regardless of race. All Americans—including rural, white, and other communities—have benefited from the President’s focus on equity. In his quest for economic justice, Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. often spoke of the challenges and experiences shared among poor white people and marginalized Black people and of how detractors sought to sow division between them to prevent unified action. Today, our politics continue to distract us from the fact that working- and middle-class Americans of all races and creeds still face a set of shared economic challenges. In his famous sermon The Drum Major Instinct, Reverend King called on us to overcome our instinct to focus on how we or our group can get ahead of others and to instead to work toward collective justice for all of those in need.

The economic data from the last two years demonstrates clearly that policies designed to support those in greatest need ultimately benefit everyone. This mirrors what social scientists call the “curb cut effect,”[3] the idea that laws designed to benefit the disabled by requiring curb cuts ultimately benefit a wide variety of groups—both disadvantaged and not—from parents with strollers to workers loading and unloading goods.

Let me highlight how this is true looking at three important indicators of economic wellbeing: (1) employment; (2) access to housing, as measured by eviction rates; and (3) access to high-speed internet, which is essential to small business formation and online education.

Expanding Employment

When President Biden took office, our country was still in the grip of a once-in-a-generation public health and economic crisis, with unemployment peaking at nearly 15 percent. Beginning with the American Rescue Plan, President Biden made it a priority to get Americans back to work. The ARP gave small businesses and governments significant resources to keep Americans on the payroll during the worst stretch of the pandemic and to invest in workforce training and other programs to support American workers in the long run.

I’ve seen these investments firsthand, on trips across the country to places like Orlando, Florida; Bethlehem, Pennsylvania in the Lehigh Valley; and many other communities. Last year, I met a woman named Diamond who almost lost her home during the pandemic. Her access to federal eviction prevention funds helped her keep a roof over her head and enabled her to enroll in job training and transition to a new career to better support her family. And there are countless more stories[4] about how the President’s response to COVID helped American workers weather the pandemic and ultimately emerge even stronger.

More recently, Treasury has implemented provisions of the IRA that provide bonus incentives for clean energy and manufacturing investments in low-income and former coal communities—helping to generate employment opportunities in these areas and enabling them to participate in the gains of the clean energy transition. Though many of these communities have significant minority populations, in numerous cases low-income white Americans will be among the primary beneficiaries of this support—especially the law’s provisions to support energy communities.[5]

These policies are emblematic of what Secretary Yellen has called “modern supply-side economics”—the idea that investing in underserved communities of all kinds is one of our best tools to create strong, sustainable economic growth. It takes as its point of departure the view that these communities have too often been left out from the investments and economic opportunities that have generated jobs and growth. But precisely because these communities have suffered from chronic underinvestment, they are poised to benefit most from the new investments our Administration is making.

The employment data demonstrates how these investments generate widespread gains—for white Americans, as well as Black and Hispanic Americans. This year, the overall unemployment rate has been near its lowest level in over 50 years, at an average of 3.5 percent. And since taking office, President Biden has added more than 13 million jobs.

At the same time, Black and Hispanic workers have seen historic gains. In the three months ending in May, the Black unemployment rate averaged 5.1 percent, the lowest three-month average on record. The average gap between Black and white unemployment also hit an all-time low, further reflecting the inclusive nature of this economic recovery.[6] Both Black and Hispanic Americans are experiencing unemployment rates well below their 50-year averages.

It is also important to highlight that the policies that created these historic gains for people of color also produced significant gains for white non-Hispanic workers and Americans living in regions with high rates of unemployment prior to the pandemic. From January 2021 to May 2023, white unemployment fell from 5.7 percent to just 3.3 percent. Over the same period, the white labor force participation rate increased by a full percentage point.

The President’s focus on protecting workers and supporting a strong labor market extends beyond gains in the number of Americans employed. These jobs have also been coupled with strong wage gains, especially for those at the bottom of the income distribution. From 2020 to 2022, workers at the 10th percentile saw their wages rise nearly 6 percent even after accounting for inflation.[7]

Preventing Evictions and Poverty

AS we’ve recovered from a global pandemic, the Biden-Harris Administration has focused on helping vulnerable Americans avoid the worst-case outcomes, from falling into poverty to facing an eviction. One of the lessons learned from the Great Recession was that these outcomes often expose those who experience them to economic scarring: long-term damage to the economic situations and prospects of individuals and families who suffer shocks like job loss, eviction, or homelessness.

The pandemic created acute risks in vulnerable communities across the country, especially the low-income communities and communities of color that disproportionately suffered from COVID-19 and its economic effects. The Biden-Harris Administration took immediate steps to address these risks through efforts like the Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) program, which provided tens of billions in rental support to vulnerable households at risk of eviction. Since 2021, in concert with the Administration’s other housing support policies, ERA has helped prevent millions of evictions. Moreover, eviction rates have remained below their pre-pandemic levels through the beginning of 2023—even after pandemic-era actions like the eviction moratorium expired.

Historically, evictions have been a particular risk for renters in communities of color. Although they make up only 20 percent of all renters in the United States, Black renters historically have accounted for one-third of evictions.[8] ERA support has particularly benefited these renters: Black families received 46 percent of ERA assistance. Extremely low-income renters have also received close to two-thirds of all ERA assistance.

But overall, white renters comprise nearly half of all evictions—the largest share of any group. As these policies have driven down eviction filings and kept Americans in their homes, millions of white Americans have benefited. From 2020-2021, while federal eviction prevention resources were available, the eviction filing rate for white neighborhoods was just 1.8 percent, well below its historical average of 3.7 percent.[9]

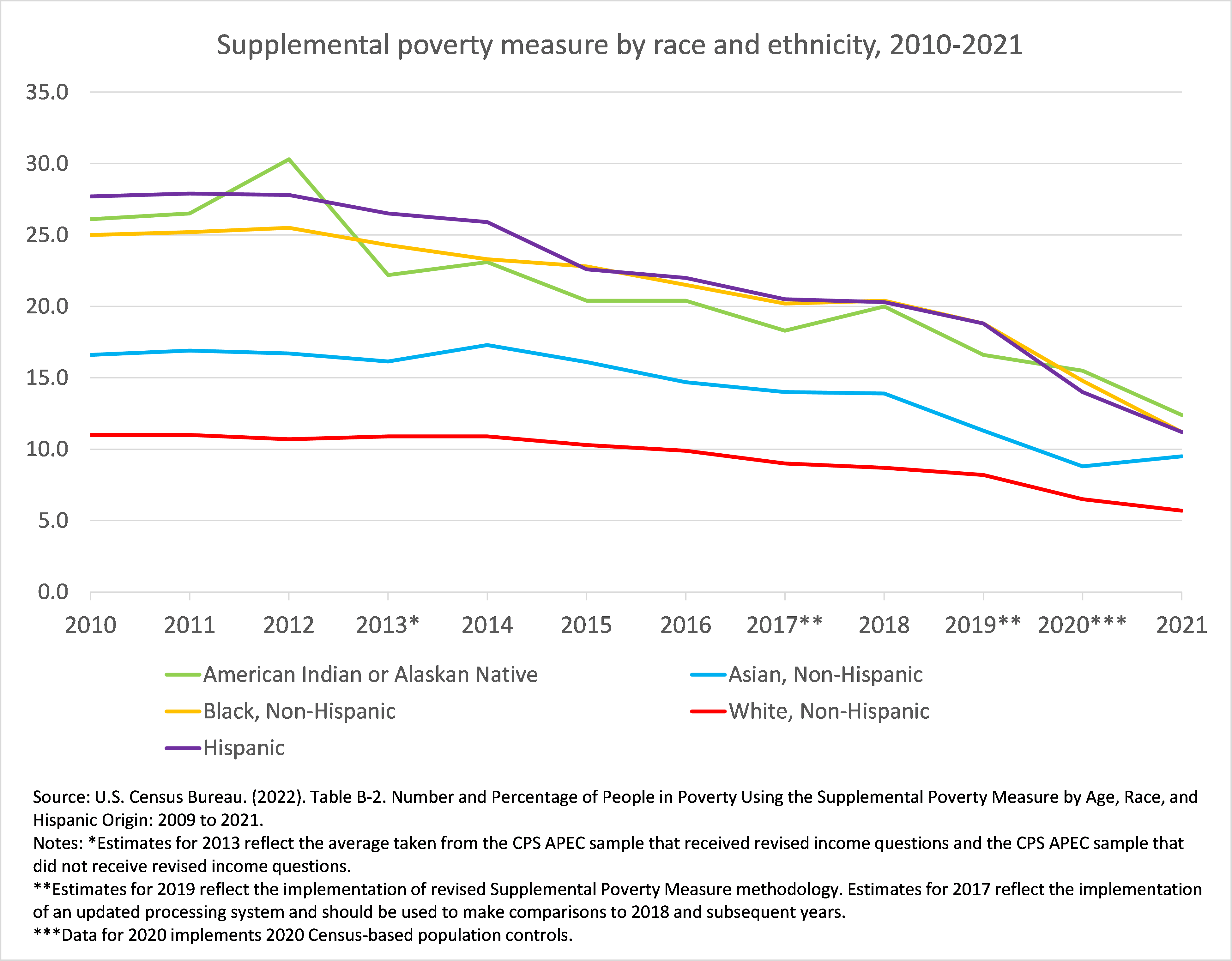

The data on poverty rates tells a similar story. Policies like the ARP’s expanded Advance Child Tax Credit, flexible funds allocated through the State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, and others have helped put in place an economic floor for many low-income Americans and families—especially children. Child poverty fell to a record low in 2021, reaching 5.2 percent and reflecting a significant reduction from the 9.7 percent rate in 2020. This decline was felt broadly: Black, Hispanic, Asian, and white children all saw supplemental poverty rates—which account for government benefits—fall to their lowest levels since 2009.[10]

Supplemental poverty rates help show these gains by race. Black supplemental poverty fell from 14.8 percent in 2020 to 11.2 percent in 2021; the Hispanic rate fell from 14 percent to 11.2 percent; and the white rate fell from 6.5 percent to 5.7 percent. These gains translate to millions of Americans lifted out of poverty across the country.

Building Broadband Access

This same dynamic also played out in our efforts to achieve universal broadband access. Broadband internet is a prerequisite for full participation in the modern economy; without it, whole swaths of the job market and critical educational opportunities are out of reach. When schools and small businesses were forced to shut their doors due to the pandemic, reliable broadband internet was a lifeline for many students and small business owners. For those without, it became yet another barrier. One study found that eighth graders with full access to technology were roughly 27 months ahead of their classmates without reliable technology access during the pandemic.[11]

Expanding access to high-speed internet will be the electrification of the 21st century, bringing economic opportunity to regions that have long faced barriers to full economic participation. Studies have estimated that every dollar spent on rural broadband access can result in three to four dollars of economic benefit.[12] That’s why President Biden is investing $65 billion to provide the infrastructure needed to ensure all Americans can access reliable, high-speed internet through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, as well as tens of billions more under the American Rescue Plan’s Capital Projects Fund and State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds.

When President Biden took office, more than 30 million Americans lived in areas without adequate broadband access.[13] These disparities tend to affect low-income Americans most but are especially concentrated in two types of communities: people of color in urban areas, who account for 75 percent of those without broadband in urban counties, and white people in rural areas, who account for 75 percent of those living without broadband in the most rural quarter of U.S. counties.[14]

These investments are already paying dividends in rural communities like Gadsden, Texas where they are using $27 million in American Rescue Plan funds to provide broadband access. This will mean that more than 5,000 students in Gadsden will have access to high-speed internet for the first time, along with farmers and small business owners who will be able to sell goods and services to customers far from their small community.[15]

Our efforts to provide universal broadband will provide an economic lifeline to these communities—and they will be transformative. In March, U.S. Treasurer Chief Marilynn Malerba received a call placed through a cell phone tower built in the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma using American Rescue Plan funds that will provide broadband access to the community of Kenwood, OK for the first time. Before this tower was built, residents of this community had to drive ten minutes to place a cell phone call, to say nothing of broadband access. And there are stories like this all over the country—in Tribal communities, urban and rural communities, Black and white communities.

Conclusion

During the Jim Crow era, many segregated communities pursued what Heather McGhee has called “drained-pool politics.”[16] In order to prevent Black and white residents from swimming in the same pools, these communities drained their pools entirely, preventing anyone from enjoying them. While this strategy excluded Black Americans, it also harmed many poor white Americans who could not afford to join the country clubs or private pools where wealthy whites continued to swim on hot days.

Drained-pool politics is emblematic of the ways that a zero-sum approach can harm Black, Latino, Asian, Native and white Americans alike. The President’s strategy provides evidence for the converse: that policies designed to improve the lives of those in greatest need, including to advance racial equity, do tremendous good for communities of color and white communities alike. The track record we’ve built—from employment to poverty and eviction prevention to broadband access—has demonstrated the truth of this view and will offer evidence to support further policies in this model going forward.

[1] Weekly and Hourly Earnings from the Current Population Survey, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[2] https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/09/record-drop-in-child-poverty.html#:~:text=In%202021%2C%20the%20child%20poverty,2009%20to%208.1%25%20in%202021.

[4] https://app.high.powerbigov.us/view?r=eyJrIjoiYTNjNzQ4MGQtM2ExZC00N2QxLWE2YTAtYmI0MmIwNmRmZDMyIiwidCI6IjU4ZjFlM2ZhLTU4Y2ItNGNiNi04OGNjLWM5MWNhYzIwN2YxOCJ9

[10] https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/09/record-drop-in-child-poverty.html#:~:text=In%202021%2C%20the%20child%20poverty,2009%20to%208.1%25%20in%202021.

[11] https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/even-pandemic-students-limited-technology-access-lagged-behind-their-peers

[12] https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/community_development/community_scope/2020/comm_scope_vol8_no1

[13] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/12/22/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-mobilizes-resources-to-connect-tribal-nations-to-reliable-high-speed-internet/

[14] Staff calculations using data from the 2021 American Community Survey. “Urban counties” are defined to be the counties in the top quartile of population density, and “most rural” are the counties in the bottom quartile. For this statistic, “people of color” are non-white or Hispanic, and “white” refers to white and non-Hispanic.