On December 8, 1860, Secretary Howell Cobb wrote to President Buchanan, “I should no longer continue to be a member of your Cabinet. In the troubles of the country consequent upon the late Presidential election, the honor and safety of my State are involved…The evil has now passed beyond control, and must be met by each and all of us under our responsibility to God and our country”.[1] Cobb left the Department of the Treasury in a state of disarray, with the South Wing extension unfurnished and the West Wing project completely halted, with slabs and columns of stone lining Pennsylvania Avenue (Figure 1: 1857, Construction of the West Wing foundation, L.E. Walker).

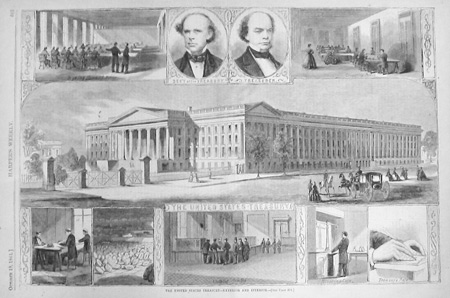

In fact, the West Wing expansion spanned seven Secretaries including Cobb, Phillip F. Thomas, John A. Dix, Salmon P. Chase, William P. Fessenden, and Hugh McCulloch and was led by four different architects, Thomas U. Walter, Ammi B. Young, Isaiah Rogers, and Alfred B. Mullett. As the capital city prepared for inevitable war, they feared that there was a conspiracy to seize the Treasury and the Capitol, thus attempting to establish the Confederate government in the hallowed halls of Union strongholds.[2] When Lincoln assumed the Presidency and the Civil War officially began in 1861, the Treasury building became so much more than a fortress of finance. Between 1861 and 1865, the West Wing of the Treasury was completed, symbolizing the strength of the Union through turbulent times. During this time, the Treasury Building served as not only a barricade and barracks for soldiers but a site of new innovation and the temporary White House for Johnson after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

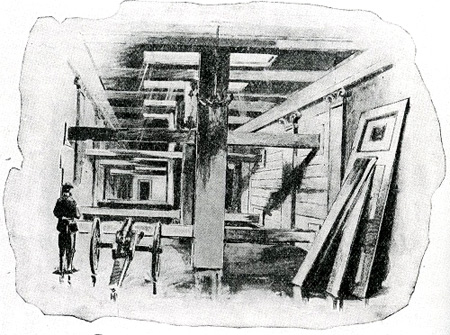

Before Lincoln took office, it had been decided by General Winfield Scott and Charles P. Stone that the Treasury would be used as an army barricade because of its sheer size, resources, and newly built basement that could serve as the Presidential bunker (Figure 2: 1861, Barricade in the basement of the West Wing).[3]

In a Washington Post article written by Stone himself, he writes:

The citadel of this center is the Treasury building. The basement has been barricaded very strongly by Capt. Franklin, of the Engineers, who remains there at night and takes charge of the force. The front of the Treasury building is well flanked…in case of attack, [troops stationed on the city’s north side will] fall back and finally take refuge in the Treasury building…in the Treasury building are stored two thousand barrels of flour, and perhaps the best water in the city is to be found there. [4]

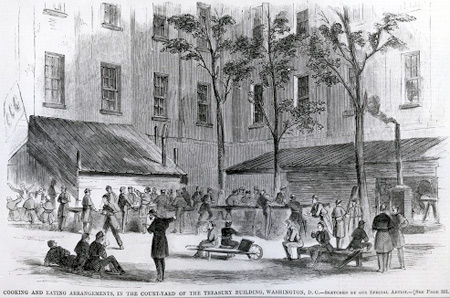

Armed troops surrounded the buildings at all times and the Treasury Department allowed the War Department to create dormitories for the guards within the building itself.[5] Regiments from various Union states took their place on the Treasury grounds, including Colonel Samuel C. Lawrence and his Fifth Massachusetts Regiment who set their barracks in the southwest corner of the building.[6] The building was prepared for war and served as a central barricade and living quarters for the Union soldiers attempting to protect Washington D.C. from the Confederate rebels (Figure 3: 1861, Union soldiers in their Treasury courtyard for meals, May 25, 1861, “Special Artist”).

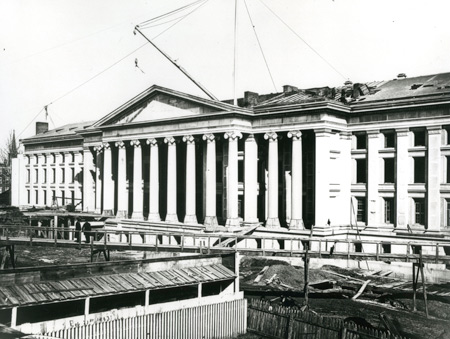

Construction on the West Wing resumed in January of 1862 due to an increase in business, the need for more space for office space, and room for Treasury Note manufacturing, thanks to the National Currency Act of July 1861 which authorized “greenback” issuance (Figure 4: 1862, West Wing construction resumes, L.E. Walker). In May, construction resumed in full with the New York Times remarking that “most of the granite columns which have encumbered Pennsylvania-avenue, in front of the White House, for several years past, have been raised to their proper position”.[7]

Workers swarmed the building, from plasterers to riggers and stonemasons (Figure 5: 1862, Construction continues, L.E. Walker). In a circular on September 2, 1862, a few days after the defeat at Bull Run, President Lincoln declared that, “all the clerks and employees of the Civil Departments, and all employees on the public buildings will be immediately organized into Companies under the direction of Brigr. General Wadsworth, and will be armed and supplied with ammunition for the defense of the Capital”.[8] Named the Treasury Guard, over nine hundred employees would leave their posts at 3:00 in the afternoon for an hour of military drilling, in order to defend the capital at a moment’s notice.[9] In her book Reveille in Washington 1860-1865, Margaret Leech Pulitzer comments that “Guards were posted, and preparations made to transform the Treasury into a strongly defended citadel…in the wings, amid the anticipation of destruction, workmen still chipped at columns and tinkered with carvings”.[10] Life for these workers was anything but simple as they worked with their eyes and ears ready for the sound of an attack.

Why was the Treasury the fortress of major protection and not the White House? Its location, next to the White House, made the Treasury Department the perfect place to hold soldiers but General Scott made sure that it was so much more than that. In the same Washington Post article of 1864, General Scott commented to Charles P. Stone that, "All else must be abandoned, if necessary, to occupy, strongly and effectively, the Executive Square, with the idea of finally holding only the Treasury building…and should it come to the defense of the Treasury building as a citadel, then the President and all the members of his Cabinet must take up their quarters with us in that building! They shall not be permitted to desert the Capital!" [11] The Treasury, since its conception in 1789, was a symbol of economic strength and prosperity for the nation. Its first two buildings, both on the same site as the current structure, were destroyed by British attack in 1814 and employee negligence in 1833 respectively.[12] When the present building’s original structure, now the East Wing, was built in 1836, it was imperative for the building to represent the strength of the nation and to be able to withstand the test of time and the elements, specifically fire. The Treasury building was indeed the best option for a war barricade and citadel for the capital city because of its physical construction and its prepared resources (Figure 6: 1863, West Front construction, L.E. Walker).

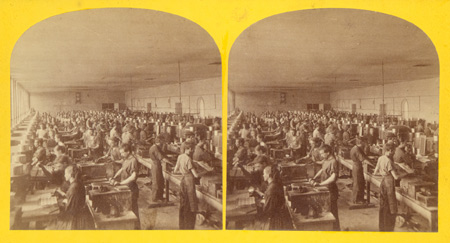

When the National Currency Act was passed in July 1861, it allowed the federal government to issue paper money. These “greenbacks” were printed off-site and shipped to the Treasury where they had to be separated and individually signed by Treasury clerks, thus creating a factory-system. This method required secure supervision and large amounts of space in order to process notes valued over $250 million.[13] Soon after realizing the practical expenses compounded by having multiple people signing the currency giving way to forgeries, “Acting Engineer Spencer M. Clark suggested substituting mechanical signatures, a step that quickly led to printing currency and bonds in the Treasury Building on a unique paper manufactured in the basement”.[14] This innovation made the process faster, cheaper, and more mainstream, adding to Treasury profits.

While Clark continued to consult with engineers to create his new printing technology for an on-site program, Treasurer Spinner had his own innovation in mind (Figure 7: 1875, Portrait of Francis Elias Spinner [10th Treasurer of the United States], Henry Ulke).

In 1891, The Woman’s Journal reprinted an account after Treasurer Spinner's death which he had written for The Home Magazine in 1862. He wrote, “When I became Treasurer of the United States, I hunted around for a chance to carry out what were called my ‘peculiar ideas’ in regard to women. It was not long before an opportunity presented itself”. He continued on by saying, “When a banker, I had found that my wife and daughters could trim bank-notes faster and more neatly than my clerks or I could, so I used to let them do that work for me…I went to Governor Chase, then Secretary of the Treasury…and said to him that these young men should have muskets instead of shears placed in their hands, and be sent to the front, and their places be filled by women, who would do more and better work”.[15] Spinner believed that female clerks would be the answer to their printing issues and Chase allowed the change. In October of 1862, the Department of Treasury hired their first female clerk and the first female government worker in United States history, Miss Jennie Douglas (Figure 8) [16] At first they hired seven more women, but by the end of the year, there were over seventy women employed by the Treasury Department.[17]

By this time, Clark, Isaiah Rogers’ Acting Engineer, had discovered a process for printing and completed a trial run that impressed Secretary Chase. The push to finish the west wing continued, “attic stories were the first priority and Rogers adapted his designs accordingly. The west wing’s attic was built as normal construction progressed, followed quickly by alterations to those in the other wings”.[18] As expenses rose for the wing’s completion and a fatal accident occurred, injuring several and killing one worker, an intense investigation of the project began. Amidst all of this, by September of 1865, the new machine called the “Fourdriner” was running perfectly, printing currency, paper, and envelopes for the Department (Figure 9: 1861).[19]

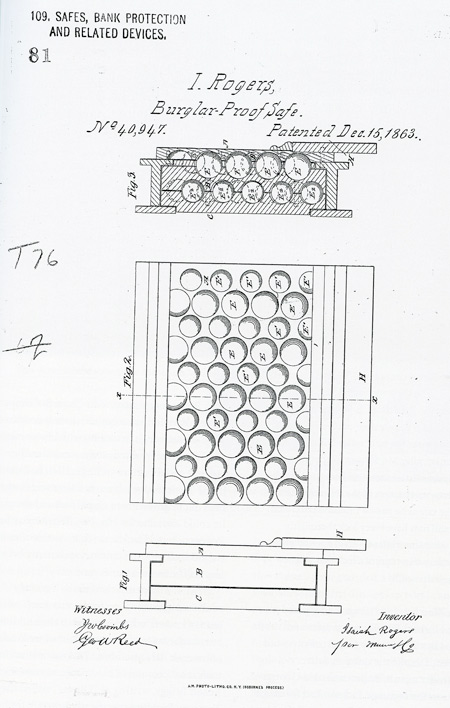

As the West Wing construction continued in 1862, Clark decided to research the vaults and safes of the Treasury Building. He traveled to various bureaus and sub-treasuries in order to see the different designs, techniques, and successes of their innovations. By April of 1863, head-architect Isaiah Rogers, “wrote an unusual advertisement for safes for west wing offices. Instead of stating that specifications and drawings made by the Bureau of Construction would be sent to competitors, he asked manufacturers to submit descriptions ‘accompanied by drawings showing the mode of construction, and full size sections of the material used’”.[20] This, Rogers hoped, would prevent thieves from obtaining drawings and would secure the latest technology in the industry. Secretary Chase added to the clause by requiring a test sample be submitted to a locksmith in New York. In the end, they chose Jackson & Company to design the Comptroller of the Currency's vault. [21] The multiple submissions also helped Rogers in conceiving his own modification which included a new lining system for “burglar proof safes” which consisted of two layers of cast iron balls with layers of iron and steel plates (Figure 10: 1863, Isaiah Rogers’ patent for a “burglar proof” vault). The balls would move freely if in contact with a drill, thus protecting it from burglars. Four in total were added to the West Wing for the Treasurer of the United States and the Comptroller of the Currency. [22] Although the vaults were not completely sound and required constant upkeep and testing, rumors spread throughout the region of the magnificent vaults and safes of the Treasury that held silver, jewels, banknotes, and so much more.[23]

What was within the vaults of the Treasury’s West Wing was not the only expensive measures of the building. Months after construction resumed on the Treasury’s new wing, Mr. Sargent of the Committee of Expenditures on Public Buildings called into question the expense and quality of the new structure. In the House Report No. 137 of the 37th Congress on July 10, 1862, Mr. Sargent wrote, “The work on the Treasury extension is illy done, insecure, and unsubstantial. The original designs are not being carried out, but are varied from in many particulars, which largely increase the cost to the government and lessen the value of the building.”[24] The plans for interior decorating included elegant French and English-inspired fixtures with American symbolism etched in the architectural structure. Architectural historian and author Pam Scott wrote that, “The creation of these elaborately decorated rooms in the west wing of the Treasury Building had occurred at the height of the Civil War, reflecting perhaps both the growth of the department and rapidly changing American tastes that favored elegant public interiors befitting the importance of their occupants.”[25] Despite much scandal and controversy over fraud and overspending, the Treasury’s construction pushed on with its sophisticated designs.

Designs for the West Wing included a new office space for the Secretary of the Treasury. Originally intended for Secretary Cobb, before his resignation to join the Confederate cause, the office was restyled when it came time for furnishing. The Secretary at the time, Salmon P. Chase, hoped the office would reflect Republican simplicity, in order to diminish the controversy. Supervising Architect Rogers, allowed a young architect, Alfred B. Mullett, to design and decorate many parts of the West Wing, including the Secretarial Suite. Pottier & Stymus of New York was chosen as the firm to deal with the furnishings and placement of the three-room office. The total expense was estimated at $5,158.44; not an atrocious cost at the time but definitely expensive. The estimate came a month before the workmen went on strike due to a change in hours without a change in wages. As Pam Scott explained, “While the Treasury’s workmen were having difficulty housing and feeding their families, and the Civil War was at a critical juncture, there was frenzied competition among the department’s bureau heads and clerks for the most impressive office furnishings” with the Secretary’s office being at the top of the list.[26] The Secretary’s office had to gleam with prestige, no matter the cost.

How much Chase knew of his new office and its expense is still a mystery but that winter, while Mullett was away, Chase took a peak at his new office. He immediately wrote a letter to Mullett saying, “I have to express my decided disapprobation of the expense you have incurred in finishing them; they are in my opinion entirely too ornate for a Public Office, and a violation of that Republican simplicity I desire you to observe in finishing and furnishing this Building.”[27] He went on to say that the arrangement for a bath off of the office was to not happen. Chase told Mullett that he would have to make the necessary changes immediately and without question. However, much to Chase’s dismay, the “furnishing work continued unabated” because of contract restrictions with Pottier & Stymus.[28] Ironically, after the project’s completion, Chase asked Mullett to change the carpet of the “Blue Room” without much question of cost. Six weeks later, Chase submitted his resignation to President Lincoln without serving a single day in his new office.[29] In his own reflections of Chase in the Treasury, Maunsell B. Field wrote, “Mr. Chase had consented to make the change; but after the new rooms were ready he delayed removing. Several times he appointed a day to do so, but when the time came he had changed his mind…I told that there was at least one obvious advantage in the exchange that that was, if he should come to these offices, he would always be able to keep his eye upon the White House!” [30] Chase went on to attempt to wrest the Republican nomination away from Lincoln in the 1864 election.[31]

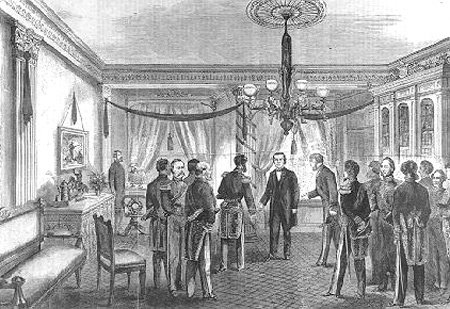

When designing the three rooms that created the West Wing Office of the Secretary, little did Rogers or Mullett know that their sitting room would one day serve a greater power. On the fateful morning of April 15, 1865, just days after the Civil War was deemed over with the Union as victors, Abraham Lincoln died from gunshot wounds he suffered the prior night. He was shot in his booth at Ford’s Theater by John Wilkes Booth who then tried to escape by jumping from the booth onto the stage. While jumping, Booth caught his spur on the Treasury Guard flag that was decorating the booth and broke his leg when he landed. With the President dead, Vice President Andrew Johnson took the oath of office and hurried to the Treasury building where he held his first meeting with his Cabinet (Figure 11:1865, First meeting of Johnson’s Cabinet in the Treasury’s West Wing after the assassination of Lincoln).

In order to give Mary Todd Lincoln, the First Lady, time to grieve and organize her belongings, Johnson operated his White House from McCulloch’s sitting room in the West Wing of the Treasury for six weeks after the assassination.[32] During this period, Johnson met with delegations from around the country, diplomats from around the world, and formulized his plans of action. Many say that while he worked in the Treasury building, Johnson never sat down

In his book, Men and Measures of Half a Century, Secretary McCulloch commented on Johnson’s presidency in the Treasury saying:

For six weeks after he (Johnson) became President, he occupied a room adjoining mine and communicating with it. He was there every morning before 9 o’clock and rarely left before 5:00 p.m. There was no liquor in his room. It was open to everybody. His luncheon, when he had one, was, like mine, a cup of tea and a cracker…It was in that room that he received the delegations that waited upon him and the personal and political friends who called to pay their respects…It was there that he made the speeches which startled the country by the bitterness of their tone- their almost savage denunciations of secessionists as traitors who merited the traitor’s doom.[33]

After meeting with grieving constituents and devising a plan to find and persecute those responsible for the murder, Johnson had to decide what to do with the ailing nation. (Figure 12: 1865, President Johnson’s first ambassador reception on April 20, 1865 in McCulloch’s sitting room. Albert Berghaus).

It was a turbulent time, as the South was bitter and the North wanted revenge. On May 29th 1865, he made his legendary reconstruction proclamation from his office in the Treasury. With Lincoln as his internal guide, Johnson changed his own fate and that of American history by writing, “To the end that the authority of the Government of the United States may be restored and that peace, order, and freedom be established, I, Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, do hereby grant to all persons who have participated in the existing rebellion, amnesty and pardon with restoration of all rights of property except as to slaves.”[34] Reactions to this historical proclamation shook the nation, North and South, to its core. On June 10, 1865, Andrew Johnson left his office in McCulloch’s sitting room and moved into the White House. Less than three years later, Andrew Johnson would leave the White House as the first impeached President.

Originally conceptualized in 1857 and abandoned by Secretary Cobb until 1862 when demand pushed construction forward, the West Wing served as a symbol of the nation’s strength and continuous growth. Despite funding issues, workmen’s strikes, fraud controversies, seven secretaries and four architects, the Treasury’s construction continued and accelerated. Innovation flourished as the department began to print and sign its own currency and the Treasury became the first federal employer of women. Serving as the potential bunker for President Lincoln and Johnson’s White House office for six weeks, the West Wing of the Treasury building became the citadel of Washington. While some revere the Capitol’s finished dome as emblematic of the Union victory, the completion of the Treasury’s West Wing truly reflects the strength of America’s federal bureaucracy that helped win the war.

[1] Howell Cobb, “The Resignation of Secretary Cobb. The Correspondence,” New York Times, Written December 8, 1860, Published December 14, 1860.

[2] Pamela Scott, Fortress of Finance: The United States Treasury Building (Washington, DC: Treasury Historical Association, 2010), p.181-182.

[3] Ibid., p.182.

[4] Charles P. Stone, “The Capital in Danger,” Washington Post, June 8, 1884, p.6.

[5] Pamela Scott, p.183.

[6] Ibid., p.187.

[7] “News from Washington,” New York Times, May 22, 1862, p.5. Monthly Report, June 1, 1862, box 1439.

[8] James S. Wadsworth, “Circular,” September 3, 1862, box 1439, entry 26, RG 121, NACP.

[9] Pamela Scott, p.188.

[10] Margaret Leech Pulitzer, Reveille in Washington 1860-1865 (New York: Harper & Brothers Pub,1941), p.58.

[11] Charles P. Stone, p.6.

[12] Department of Treasury, Office of the Curator, Treasury Building Tours: A National Historic Landmark, Docent Manual (Washington D.C., 2011).

[13] Pamela Scott, p.190.

[14] Ibid., p.199.

[15] “General Spinner and the Women Clerks,” The Woman’s Journal, Vol. XXII, No. 2, Page 16, cols 1 and 2, Library of Congress, Microfilm 51565, Reel 192.

[16] General Spinner, The Washington Post: Sunday June 19, 1887, p.6, columns 3 and 4.

[17] Treasury Women 1795-1975, from Sarah to Anita, Treasury File.

[18] Pamela Scott, p.200.

[19] Ibid., p.202.

[20] Ibid., p. 206.

[21] Ibid., 208.

[22] Department of Treasury, Office of the Curator, Treasury Building Tours: A National Historic Landmark, Docent Manual (Washington D.C., 2011).

[23] Emily Edson Briggs, The Olivia Letters (New York: Neale Publishing Company, 1906), p.223.

[24] Mr. Sargent, “Expenditures on public buildings” United States House of Representatives, House Report No. 137, 37th Congress, 2nd Session, July 10, 1862.

[25] Pamela Scott, p.218-219.

[26] Pamela Scott, p.225.

[27] Salmon P. Chase to Mullett, February 1, 1864, box 1448, entry 26, RG121, NACP

[28] Pamela Scott, p.222.

[29] Ibid.,223.

[30] Maunsell B. Field, Personal Recollections, Memories, and Many Men and Some Women (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1874), 281.

[31] Pamela Scott, p.225.

[32] Ibid., 218.

[33] Hugh McCulloch, Men and Measures of Half a Century (New York: C. Scribners Sons, 1889).

[34] Andrew Johnson, “Amnesty Proclamation” (Washington D.C., May 29, 1865).

[35] Pamela Scott, p.214.

[36] Margaret Leech Pulitzer, p.58.