By Assistant Secretary for Tax Policy Lily Batchelder and Deputy Assistant Secretary for Tax Analysis Greg Leiserson

As we have written about often here, President Biden’s first executive order directed agencies to examine their policies and programs to identify whether and how they perpetuate barriers to equal opportunity. As part of this work, a team of researchers at the U.S. Census Bureau, IRS, and Treasury Department recently completed an analysis of the demographics of the recipients of the first round of Economic Impact Payments (EIPs) paid in 2020 to examine potential disparities in the receipt of these payments by age, income, gender, race and ethnicity, and presence of children.[1] As with all research using tax data, this research carefully followed stringent data protection protocols to prevent disclosure of taxpayer information. This research is part of the Treasury Department’s broader, groundbreaking efforts to assess and acknowledge the impact that policies have had on various demographic groups, as such analysis is critical to informing and designing more equitable policy proposals.

Background

The CARES Act, signed into law in March 2020, provided EIPs to blunt the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. This payment was worth up to $1,200 per adult plus $500 per child under age 17. For a family of four, this payment could provide up to $3,400 in direct financial relief. Subsequent legislation in 2020 and 2021 provided a second and third round of EIPs.

The law instructed the Secretary of the Treasury to issue these payments as rapidly as possible. The Department of the Treasury acted quickly. From the day the CARES Act became law, Treasury and the IRS took only two weeks to issue the first direct deposits and only four weeks to issue the first paper checks. By nine weeks after enactment, Treasury and the IRS had issued 160 million payments to effectively all individuals who were believed by the IRS at that time to be qualifying individuals. For comparison, the last time that stimulus payments were issued in response to a major economic crisis, during the Great Recession in 2008, it took 11 weeks to issue the first direct deposit and 13 weeks to issue the first paper check. Nearly all payments were issued within 21 weeks.

To ensure that as many eligible families received the credit as possible, Congress enacted and Treasury administered a number of novel methods to expand the reach of the credit, including paying the credit on the basis of information on prior-year tax returns, paying the credit on the basis of information known to other federal agencies, establishing an online portal that allowed non-filers to file a simplified 2019 tax return to claim a stimulus payment, and mailing outreach letters to roughly 9 million non-filers who Treasury and the IRS estimated might be eligible for, but had not claimed, a stimulus payment once most payments had been sent.

Key Findings

The researchers find that 55 percent of people who received an EIP did so in the first week the payments were made, and 95 percent received their EIP within six weeks. They find that younger individuals, lower-income families, and families with children received EIPs more quickly, likely due to the higher rate at which these groups receive tax refunds via direct deposit. (In order to issue payments as quickly as possible, payments were first issued electronically to individuals who received a refund via direct deposit on the tax return used to generate their payment.) Approximately 60 percent of multiracial, Hispanic, or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander recipients received a payment in the first week, compared to approximately 55 percent of White, American Indian and Alaska Native, Black, or Asian recipients. In contrast, White and Asian recipients were the most likely to receive their payments in the first six weeks, though more than 90 percent of payments were received in the first six weeks for every racial/ethnic subgroup the authors examined.

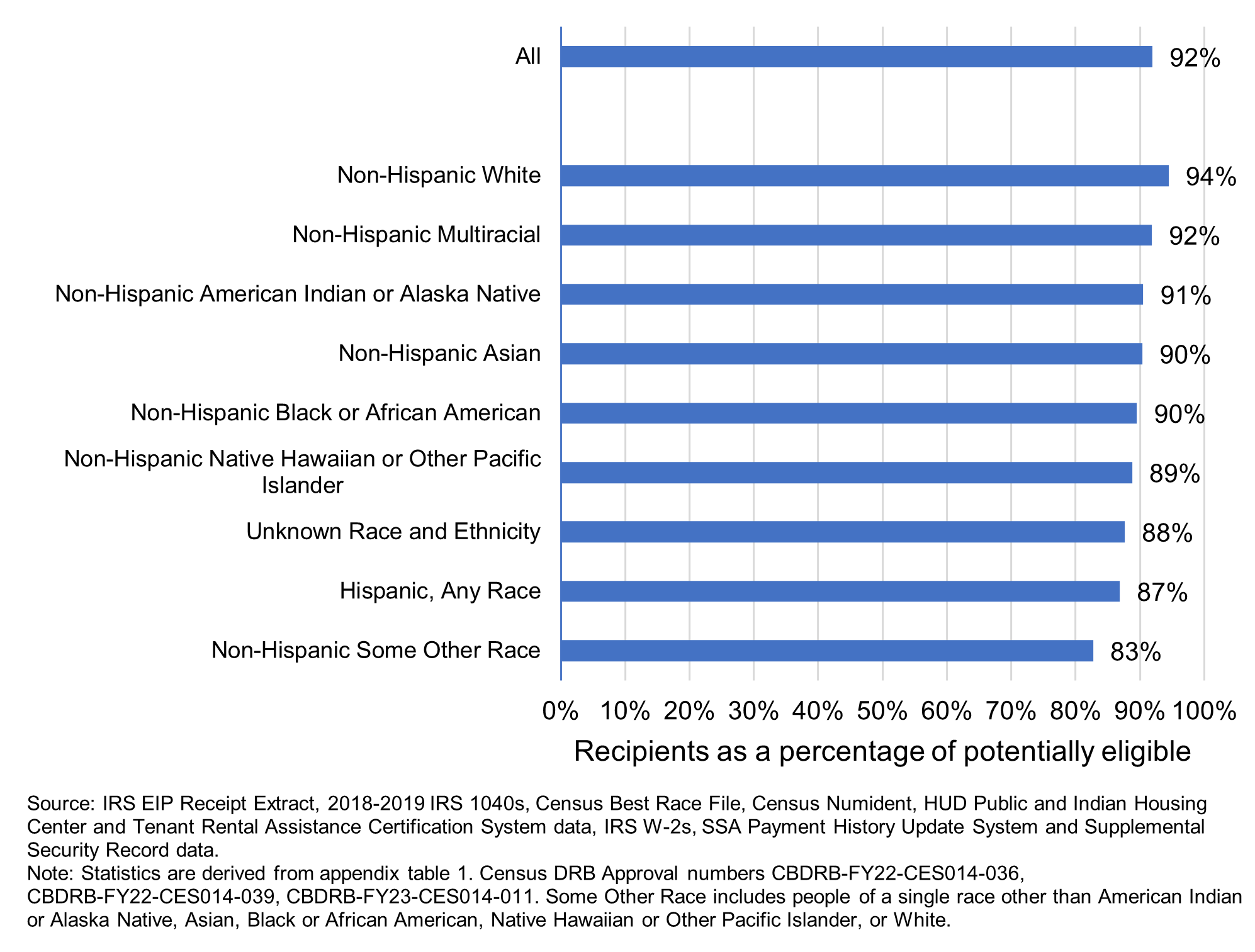

The authors estimate that 92 percent of potentially eligible individuals received an EIP, which is high when compared to estimated receipt rates for other tax credits or other non-tax benefits.[2] The estimated receipt rate was quite high for individuals over age 60, likely due to automatic payments made to Social Security recipients. The authors find that, while quick receipt was shared across racial and ethnic subgroups, there were some differences in estimated receipt rates. (See Figure.)

Figure: Recipients as a percent of the estimated potentially eligible population by race/ethnicity

Methodology and Related Research

As described in prior blog posts, this research reflects an interagency collaboration that allowed researchers to build on the strengths of the data available in different agencies. The researchers linked two confidential administrative data sources while carefully following stringent data protection protocols: Census data on race and ethnicity, and IRS data on EIP disbursement.

While the statistics on the timing of EIP receipt can be calculated directly from administrative records, the statistics on the receipt rate rely on estimates of the potentially eligible population. The researchers estimate the potentially eligible population using available data, but the actual size of the eligible population is unknown and may differ from these estimates.

This work also reflects the ongoing efforts of Treasury and the IRS to ensure that taxpayers receive the tax credits for which they are eligible.[3] The findings of this research both reflect the efforts that were undertaken to ensure that eligible people received these credits and demonstrate that there remains work to be done to reach all eligible taxpayers.

[1] Accompanying the paper is a set of tables that reports first round EIP payments for detailed demographic subgroups. These tables allow interested readers to further study outcomes for the first round EIP payments.

[2] The estimated receipt rates should be viewed as a lower bound for the true receipt rate since the potentially eligible population may be overstated.

[3] Eligible taxpayers who did not receive a first, second, or third round EIP may file or amend a 2020 (first and second rounds) or 2021 (third round) tax return to claim the corresponding 2020 and 2021 Recovery Rebate Credits. Taxpayers generally have three years from the date a return was originally due to file or amend a claim for an additional refund.