First Philadelphia Mint buildings, engraving (National Archives)

The first Mint building in Philadelphia was a modest set of buildings housing offices and manufacturing spaces. "Many citizens of the new nation were deeply suspicious of federal power. They were accustomed to using coins issued by their own state banks, along with various forms of foreign currency. The suggestion of a single federal mint producing a uniform coinage was disturbing." - Independence Hall Association

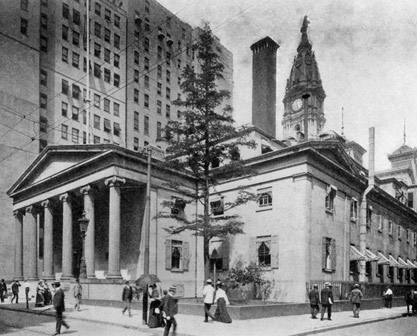

Second Philadelphia Mint building designed by William Strickland, 1833-1907.

In the late 1820s the Mint decided it needed more space to keep up with rising production requirements. The old buildings were abandoned, and in 1833 a new Mint was opened in another part of town. Designed by William Strickland, it was a simple two story building with basement in the early Greek Revival mode. A welcoming portico of Ionic columns and a grand flight of stairs invited the visitor inside.

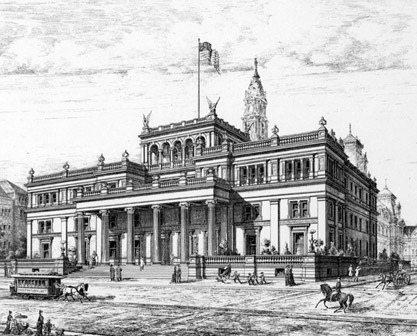

Architectural rendering of the proposed design of the third Philadelphia Mint building by William A. Freret, Supervising Architect, Department of the Treasury

After more than 60 years of service, the Mint again decided on building a larger facility for its increasing production demands. The result was the building designed in the late 1890s under the Supervising Architect's Office, Department of the Treasury.

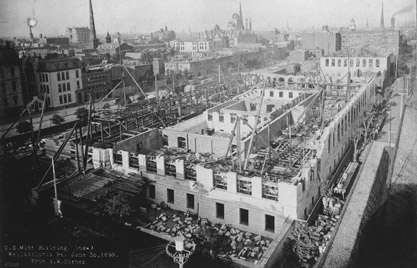

Photograph of the construction of the third Philadelphia Mint building c. 1899.

This black and white photograph is an aerial view of the third Philadelphia Mint building during construction and the surrounding buildings adjacent to the mint.

Photograph of the entrance of the fourth Philadelphia Mint building

The Bureau of the Mint built a fourth building in Philadelphia in the 1970s. Concerns over security and access to major transportation routes trumped civic presence and architectural symbolism. As one writer notes, "The latest Mint lacks the intimacy of the first Mint and the majesty of the second and third edifices. It is white, boxy, and nearly windowless." The architectural style of the fourth mint building wass Brutalism, which flourished in the United States in the late 1960s and 70s, and refers to buildings of exposed concrete, rough surfaces, and small window areas, and is dedicated to solving functional requirements above all.

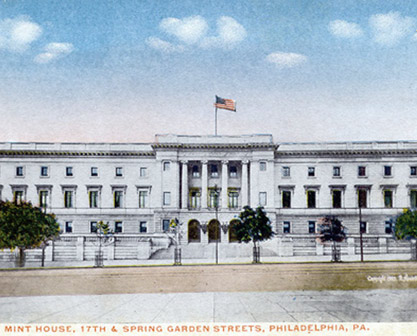

Tinted color postcard of the third Philadelphia Mint

Like the Denver Mint, Philadelphia’s third incarnation of a Mint building grew out of the American Renaissance of the late nineteenth century. During this time a revival of classical architecture swept the nation, producing classically detailed buildings, lavish interiors, and grand public spaces. According to architectural historian Richard Guy Wilson, "It was a new sense of history that most directly formed the mental set" of this period. A newfound respect for artistic riches of the Italian Renaissance of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries dominated scholarship and popular literature. Americans of the time came to see their own culture as derived from the lineage of Ancient Greece and Rome, the Italian Renaissance.

Exterior detail of the portico entrance of the Philadelphia Mint building

The architectural period of the third Philadelphia Mint was not homogenous in its production. Architectural historians have characterized the period as one of architectural "eclecticism". Many were critical of perceived problems with some of the federal buildings in the classical vein during this time.

Exterior of the entrance elevation of the third Philadelphia Mint building

Architectural historian Walter Kidney writes, "In essence, a federal building was an office building, but without floor shops and only a few stories high...On a massive basement, often heavily rusticated, half-columns or pilasters rose for three or four stories to support an entablature...Sited at one end of an enclosed open space of the right size...such a building could be quite handsome. Often, however, because of their enclosed look, their superhuman scale, their artificiality of design, and their somber materials...such buildings look self-centered and aloof, mere voids in the busy street scene. Business buildings, even banks, have an air of welcome and life that these pompous nests of officials almost totally lack."

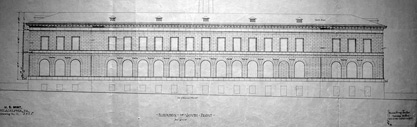

Philadelphia Mint, elevation, architects drawing

The side elevation drawing of the Philadelphia Mint displays many of the features of which architectural historians were often critical. Its saving grace, however, as with most Beaux Arts buildings, is a degree of ornament which provides human-scaled elements and lively additions to an otherwise repetitive block. The building is adorned with many beautiful and admirable details typical of Beaux Arts architecture. The main lobby is articulated with columnar arcades, a grand staircase, and a Tiffany glass mosaic ceiling. Many rooms are adorned with pilasters, murals, and marble tile or terrazzo floors. The solid and "enclosed" look was felt appropriate to its purposes as an institution of the government and economy.

Philadelphia Mint pedestrian arcade leading to the main lobby

The entrance façade of the building articulates the spatial arrangement of the rooms inside, clearly indicating the central lobby and stairs and the long hall of offices to either side of the lobby. The architecture, however, masks the industrial function of the Mint. Such a function held an awkward position in Beaux Arts theory, and in many cases of downtown buildings housing factory-like functions the exterior treatment sought to minimize the industrial presence in order to project a more decorous façade to the street.