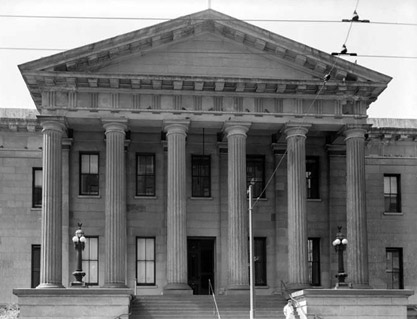

Portico Entrance of San Francisco Mint

No ornamentation has been attempted, but dependence placed on the magnitude and proportion of the building for its architectural effect. No pains have been spared to make it, when complete, not only the finest and best constructed building on the Pacific coast, but the best arranged mint in the world.” - Alfred B. Mullett, Supervising Architect

San Francisco Mint Building Interior

Designs for the Old Mint were completed by Supervising Architect Alfred B. Mullett and his staff in 1868. In 1875, Mullett's successor, William A. Potter, wrote that the costs at completion "including construction, furnishing, and machinery" amounted to $2,201,198.32. Mullett's own conclusion about the building was straightforward: "The work on the building has been done in a substantial manner, and is undoubtedly a cheap as well as a permanent structure." All along, the theme of permanency and strength had been foremost. For Mullett, a public building such as a branch Mint was to be "convenient, durable, and creditable to the government." He felt it should celebrate the strength and endurance of the institution it housed by presenting a public face of stability and grandeur. Inside the Mint, careful ornamentation and detailing provided major rooms with dignified settings for work.

Photograph of the south wing of the Main Treasury building, Washington, DC

The Old Mint is designed in an architectural vocabulary known as Greek Revival. Much like the main Treasury Building in Washington, DC, the Mint is dominated by a large entrance portico that spans the entire height of the building, and is capped by a pediment. The corners of the Mint are emphasized by stepping forward, and these “pavilions” are treated with pilasters, or flattened columns on the wall. The center, then, is clearly the most important feature, as is always the case with Greek Revival architecture. The Greek Revival style, as its name implies, takes the architecture of Ancient Greece as the supreme model. This emulation was seen as especially fit for federal buildings, which proclaim the stability and strength of national institutions. In San Francisco the choice of this architectural idiom seemed especially appropriate for a major institutional building following the city’s 1868 earthquake, when the continuity and durability of the city’s institutions needed tangible proof.

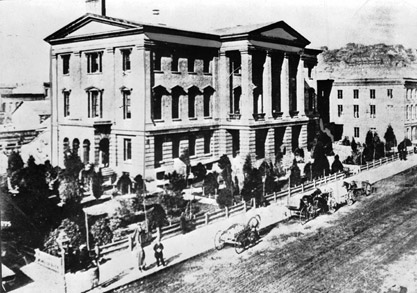

San Francisco Customhouse

Built in 1855, architect Gridley Bryant’s Custom House is often cited as the first major federal building on the Pacific coast. The building clearly demonstrates the same features of the Greek Revival that influenced Mullett’s Mint design and Robert Mill’s Treasury. In an obvious way, Mullet’s Mint is simply an expansion of the Custom House by the addition of the corner pavilions and two more columns on the portico. In addition, the Mint follows the Custom House’s distribution in two floors above a basement level. The Mint, however, adds a grand entrance stair to sweep the visitor above the basement level in a dramatic and appropriate gesture of the building’s public nature.

Old Post Office Building, St. Louis, MO

Old St. Louis Post Office and Former State, Navy, and War Building: While Greek Revival architecture seemed appropriate for the Mint, many of Mullett’s other buildings were formed by a style known as Second Empire. The two examples shown here demonstrate the most salient characteristics of this architecture: mansard roofs, strict symmetry and repetition of windows, and a “crowded” effect due to the great extent of exterior ornamental features which are set close to each other both vertically and horizontally, and which are derived from French classicism.

Eisenhower Executive Office Building, Washington DC

Eisenhower Executive Office Building (EEOB), formerly the Old Executive Office Building (OEOB) and before that the State, Navy, and War Building. The building is an example of a structure built to combine industrial and ceremonial/public spaces, the latter generally much more elaborate and finely decorated than the former. For modern day uses of the building, the integration of both types of rooms with new functions poses a challenge to adaptive reuse.

Mint Building (right) in aftermatch of 1906 earthquake and fire

The Mint building after the city of San Francisco had been engulfed by flames following the 1906 earthquake. Surviving with relatively minor damage, the Mint was a source of pride to citizens of San Francisco who saw the monumental federal building as affirmation that the city had come of age and that the state of California, only 25 years old, was nationally important.

City of San Francisco after the earthquake and fire in 1906

One witness described the 1906 earthquake like this: “The street beds heaved in frightful fashion. The earth rocked and then came the blow that wrecked San Francisco from...the Golden Gate to the end of the peninsula...A world of structural work had found a resting place on mother earth. Bent steel girders and huge blocks of decorative stone made their sleeping place beside all this.” Amid the ruins of the city, the Mint stood shaken but intact. It immediately became a “refugee village” and a center for relief aid. After the shock, as the city began to burn, workers saved the building and its holdings. This fact helped promote economic stability through quick recirculation of money and stimulated the fast recovery of the city. Before its completion, Alfred Mullett said, “The destruction...in San Francisco by earthquakes has rendered it necessary to take every precaution...and I am willing to risk my professional reputation upon its stability if properly carried out according to my plans.” His word stood vindicated in the terrible moments following the quake. Among the factors that secured the building from destruction by the quake and subsequent fires was the quick response of the fire department to douse the building in water, the efforts of mint employees and volunteers to secure the building, and, with credit to Mullett, the building’s distance from other structures, which prevented fire from quickly spreading. The structural integrity of the building also proved its merit as it suffered little damage from the quake itself.

Coins from San Francisco Mint

The Mint played an important role in financial history of the United States from 1874 until its closing in 1937: by 1934 a significant amount of the country's gold was stored at the facility and the Mint coined money for nations such as Japan, China, the Philippines and Latin American countries.

San Francisco Mint Building Exterior Stone

From 1937-57 the Mint remained under Treasury control, housing offices of the Geodetic survey, Bureau of Standards, Bureau of Mines, and Civil Service Commission, among others. A major preservation battle was fought over the building in the 1950s and 60s. Impassioned community members, architects, preservationists, and politicians called for saving the Mint. The Old Mint underwent renovations in order to be transformed into a Mint museum, which lasted from 1973 to 1994. Original circulation and room configurations were restored in the public areas, while office spaces were updated with new electrical wiring, fixtures, and suspended ceilings. The tension between manufacturing facility and public building was resolved by transforming formerly industrial parts of the building to office and storage areas, while public areas remained so.

New San Francisco Mint building completed in 1937

The old San Francisco Mint was closed as an operating Mint in 1937. The new San Francisco Mint was designed in the "stripped classicism" style by architect Gilbert Stanlay Underwood. Over time, both Mint buildings became appreciated for their architectural significance and both are on the National Register of Historic Places. Currently, the city of San Francisco is working with developers and community organizations to reopen the Old Mint to the public. Their challenge will be to make the building not only economically viable but also, and more importantly, culturally relevant once again. The trick is to find uses which guarantee public access to the most architecturally important spaces in the building while providing financial returns through commercial or private uses in less essential rooms. The city’s smart effort to encourage reuse of old buildings and sensitive infill projects in the neighborhood of the Mint speaks to the desirability of making an example of the Mint as the city grows and faces the challenges of preserving its architectural legacy.